‘The Black Clown’ with light design by John Torres

Jul. 25, 2019

In this musical theater piece adapted from a Langston Hughes poem, the bass-baritone Davóne Tines embodies the evolving, divided soul of black America.

By: Ben Brantley

The master of ceremonies has signaled that it’s time for applause now. And though the audience’s response is instant and thunderous, he is suddenly looking troubled.

Why? What we have just witnessed, in an early scene in the magnificent “The Black Clown,” was certainly applause worthy — a charming evocation of Harlem in the age of the Cotton Club, with ecstatically nimble dancers and a gardenia-sporting vocalist channeling Billie Holiday.

It seems only natural that Davóne Tines, the singer at the center of these revels, should indicate the now empty stage with a gesture that says “Aren’t they great?” But his smile is soon melting into a perplexed, doubtful expression.

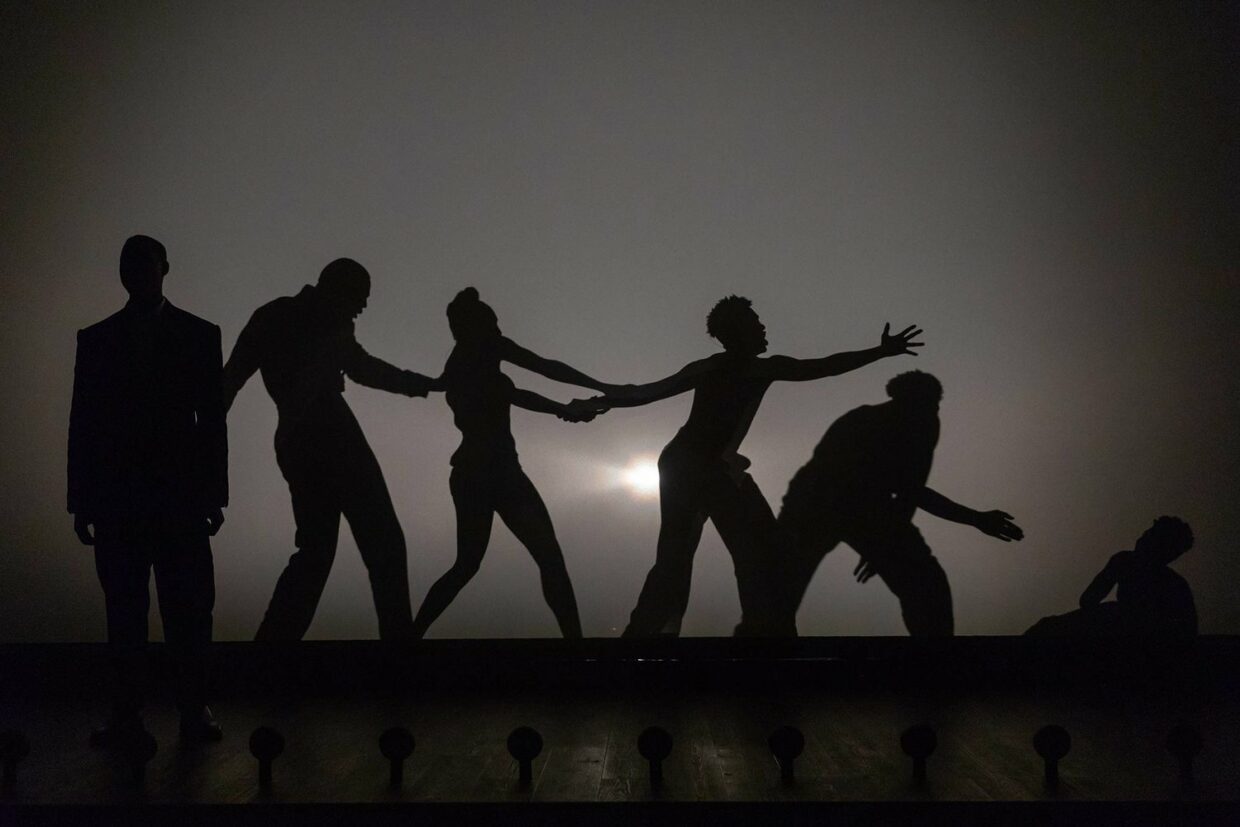

It’s a response that makes sense when the dancers reappear, in the same crouched conga line with which they had previously left the stage. They’re only silhouettes now, figures behind a vast scrim.

Their body language speaks not of elation but of a weary, ingrained fear. And the mood has shifted from the buoyancy of a number titled “Strike Up the Music” to the lumbering solemnity of a sung passage that begins “Three hundred years,/ In the cotton and the cane.”

“The Black Clown,” which opened on Wednesday (and runs only through Saturday) at the Gerald W. Lynch Theater as part of Lincoln Center’s Mostly Mozart Festival, is full of such unsettling, quicksilver reversals. Adapted by Mr. Tines and Michael Schachter from Langston Hughes’s 1931 poem, this rich, seamless production melds the past and present of African-American history into an electrifyingly ambivalent whole.

Mr. Tines, the show’s star, and Mr. Schachter, its composer, initially conceived this work as a song cycle for voice and piano. And simply to hear Mr. Tines sing Hughes’s “cry to the world,” in which a black man’s sense of humiliation shifts slowly into affirmation, as a solo performance would no doubt in itself have made for a deeply satisfying experience.

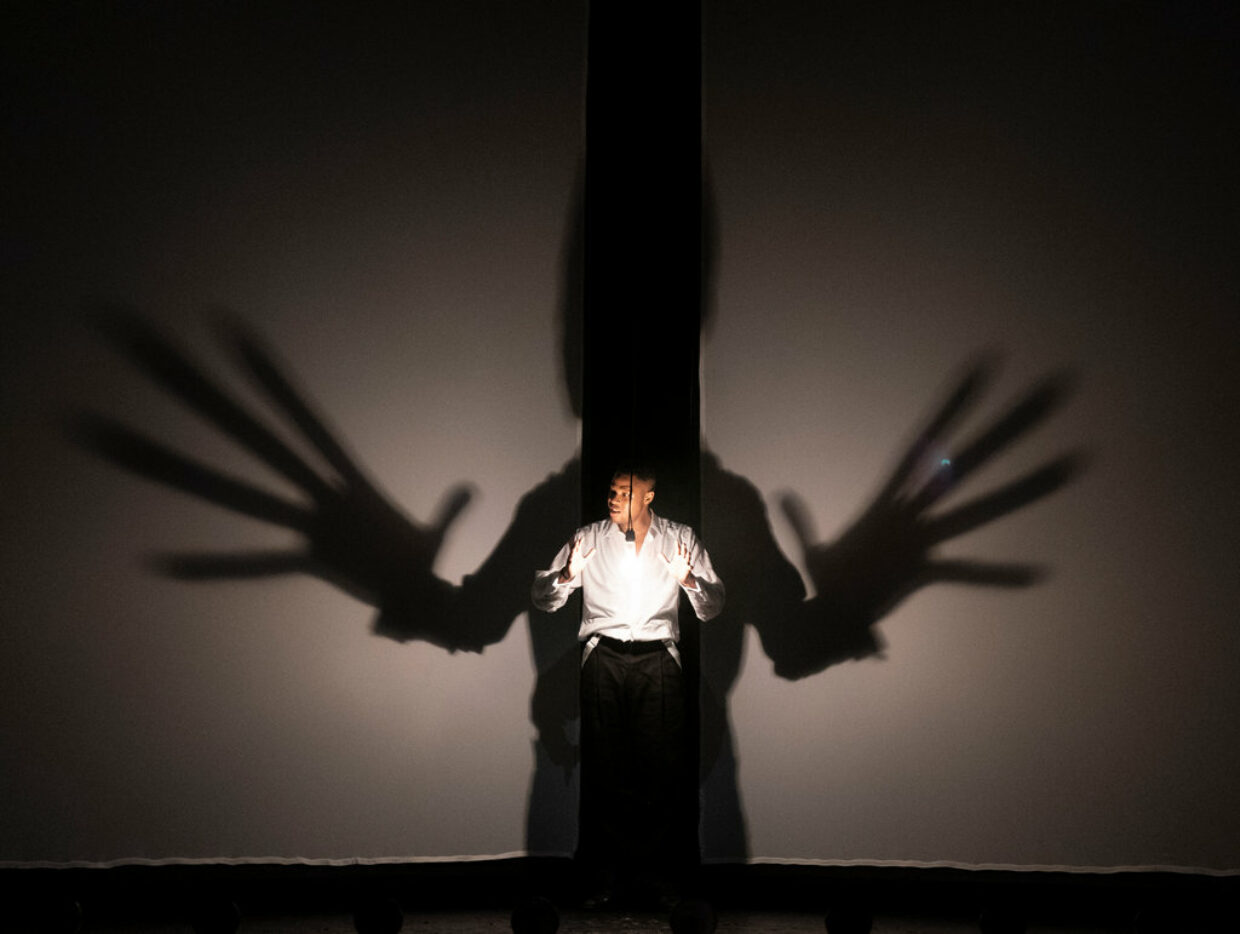

An estimable opera singer, Mr. Tines has a depths-plumbing bass-baritone that can find a range of contradictions within a single note. And his body and face match that voice in their expressiveness. Surrounding him with a dozen other performers in a full-dress production with a big band would seem be flirting dangerously with excess.

Yet as directed by Zack Winokur, with choreography by Chanel DaSilva and sets and costumes by Carlos Soto, this “Black Clown” feels like a natural extension of the single voice — and the divided self — at its center. As such, it becomes both a bravura, in-the-moment entertainment and a haunted, self-conscious questioning of the ways in which it entertains.

In that sense, “The Black Clown” is of a piece with a fertile new crop of plays that formidably include Jackie Sibblies Drury’s “Fairview,” this year’s Pulitzer Prize winner for drama. Like such works, this musical theater piece considers the ways in which the black experience has been curated and co-opted for mass consumption, and particularly for white American audiences.

It starts with the simple yet sophisticated assumption that if you repeat something — a phrase, a gesture, a melody — enough times, it acquires different meanings, shedding its original power and perhaps acquiring new strength. The process begins in the show’s first moments, when Mr. Tines delivers the opening lines.

“You laugh/Because I’m poor and black and funny.” As this commanding singer says the same lyrics again and again, he addresses us with increasing directness and delicately changing emphases, asking us to hear what he hears. And throughout, musical tropes associated with black American history — the minstrel show, the jazz riff, the work song, the gospel hymn — evolve in ways that remind us of how a single melody line can contain multitudes of feelings and meanings.

Take the use of the deathless spiritual “Sometimes I Feel Like a Motherless Child.” (Mr. Schachter’s exquisitely layered score takes many of its musical cues from Hughes’s annotations for suggested performances of his poem, printed as a separate entity under the heading “The Mood.”) In this version the song turns from a lonely lamentation into a spirited dirge for a New Orleans-style funeral into a cry of existential anguish.

Such songs can be — and are — all those things. And every aspect of the show echoes this sense of multiplicity. It’s evident within the performances, always in sync yet always personally idiosyncratic, of the ensemble of singers and dancers, and in the props they deploy.

For a sequence built around the towering apparition of an Abraham Lincoln figure (on stilts) brandishing the Emancipation Proclamation, chains are worn as if they were boas for showgirls. A long rope is deployed for jumping games and a tug of war, before configuring itself into an outsize noose.

Then there are the silhouettes of the performers, which multiply and divide as shadows cast from behind vast scrims. (John Torres did the marvelous lighting.) These are shadows of a past that is always present. Mr. Tines crosses between these realms, like a curious and conflicted spectator being claimed and transformed by that which he observes.

The screens are torn down for the show’s concluding sequence, a cathartic choral number of affirmation and individuality. But the production doesn’t entirely abandon the subtle double edge it has sustained throughout.

Its final line is not sung but spoken by Mr. Tines. Since Hughes’s poem is readily accessible (and printed in the program), I don’t think it counts as a spoiler to reveal what is said: “I’m a man!”

But listen, just listen, to how Mr. Tines delivers those three simple words, and marvel at the grandeur that can sometimes be conferred by understatement.

Source: The New York Times