Somaya Critchlow in Conversation with Dan Thawley

Dec. 3, 2020

Text by SSENSE

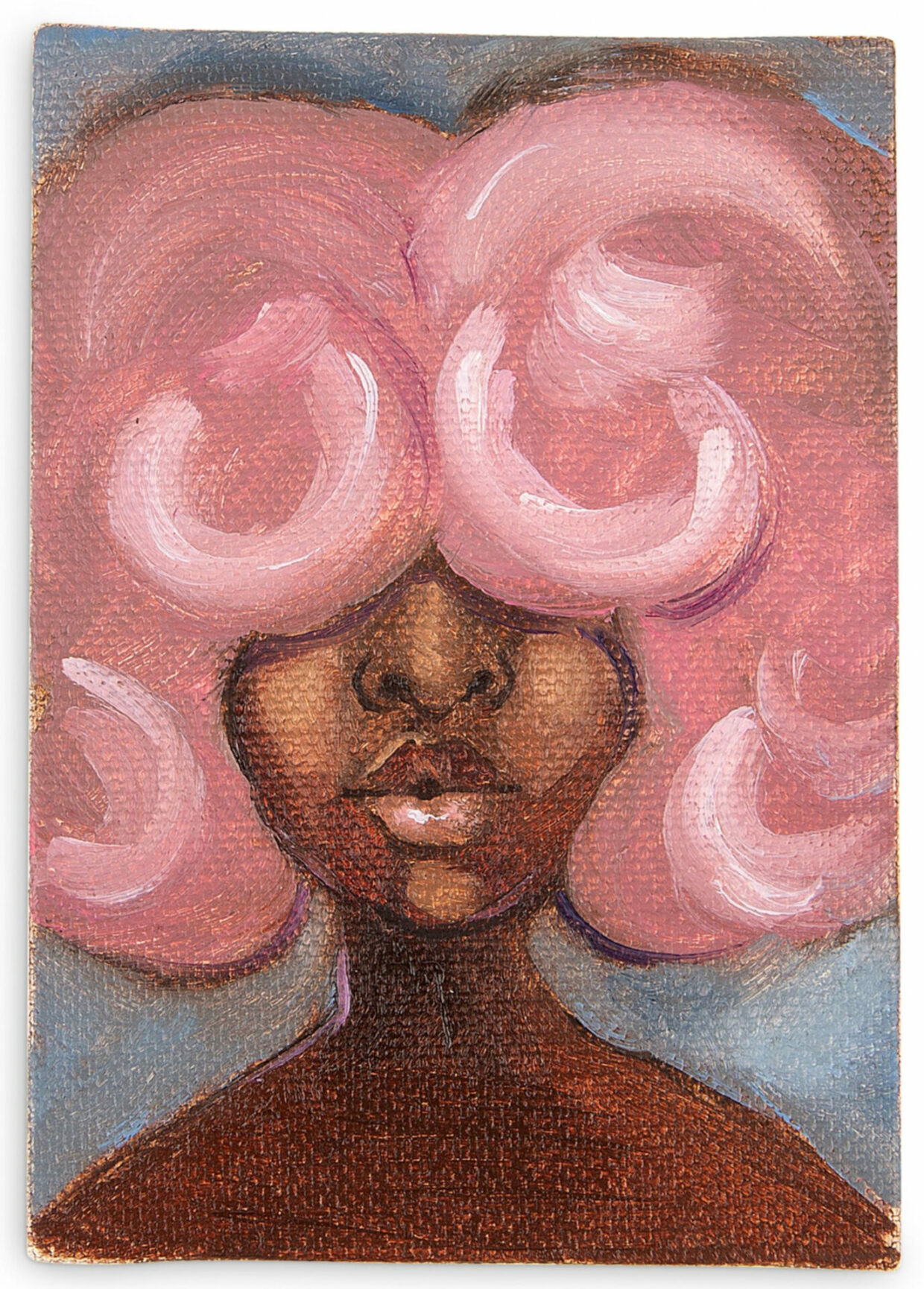

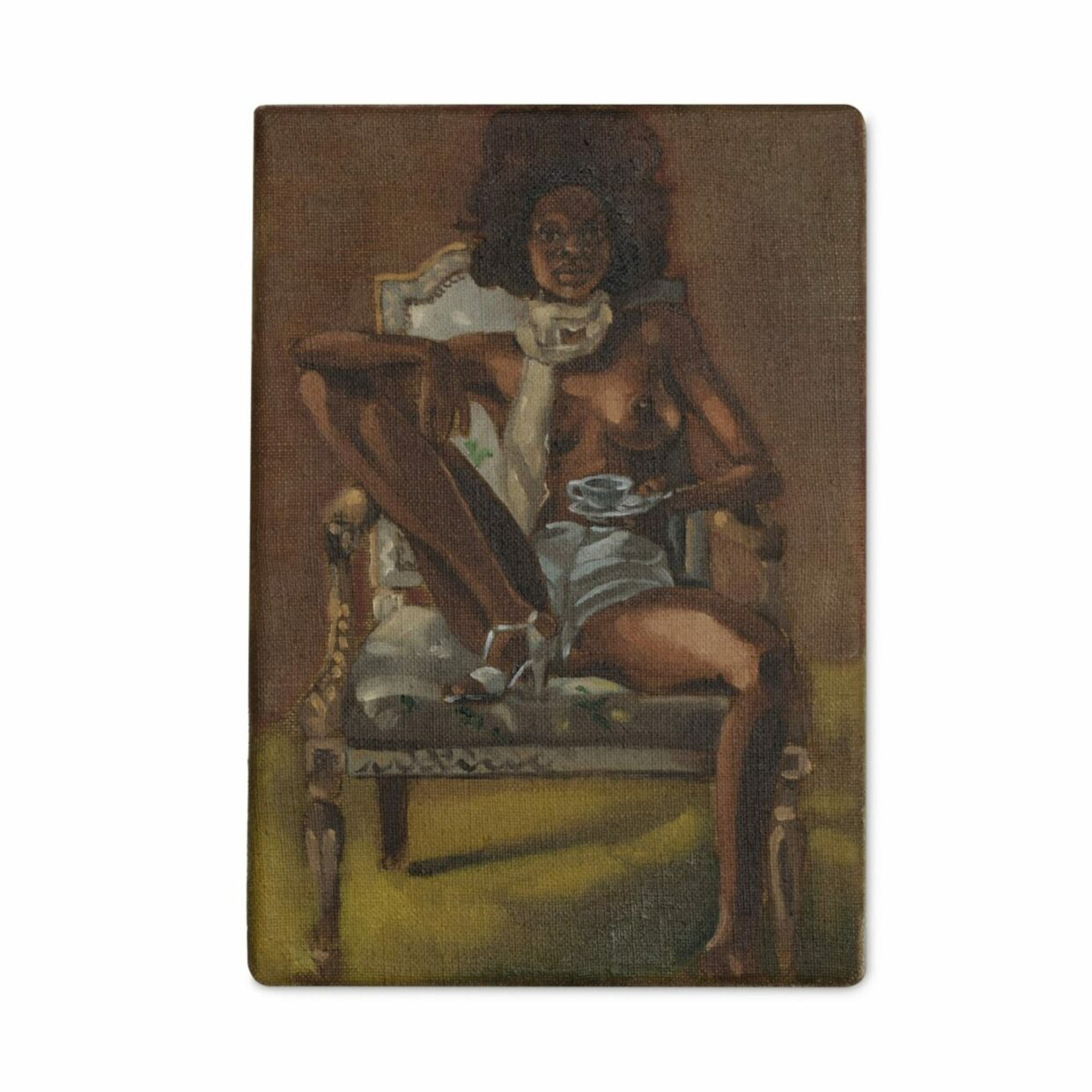

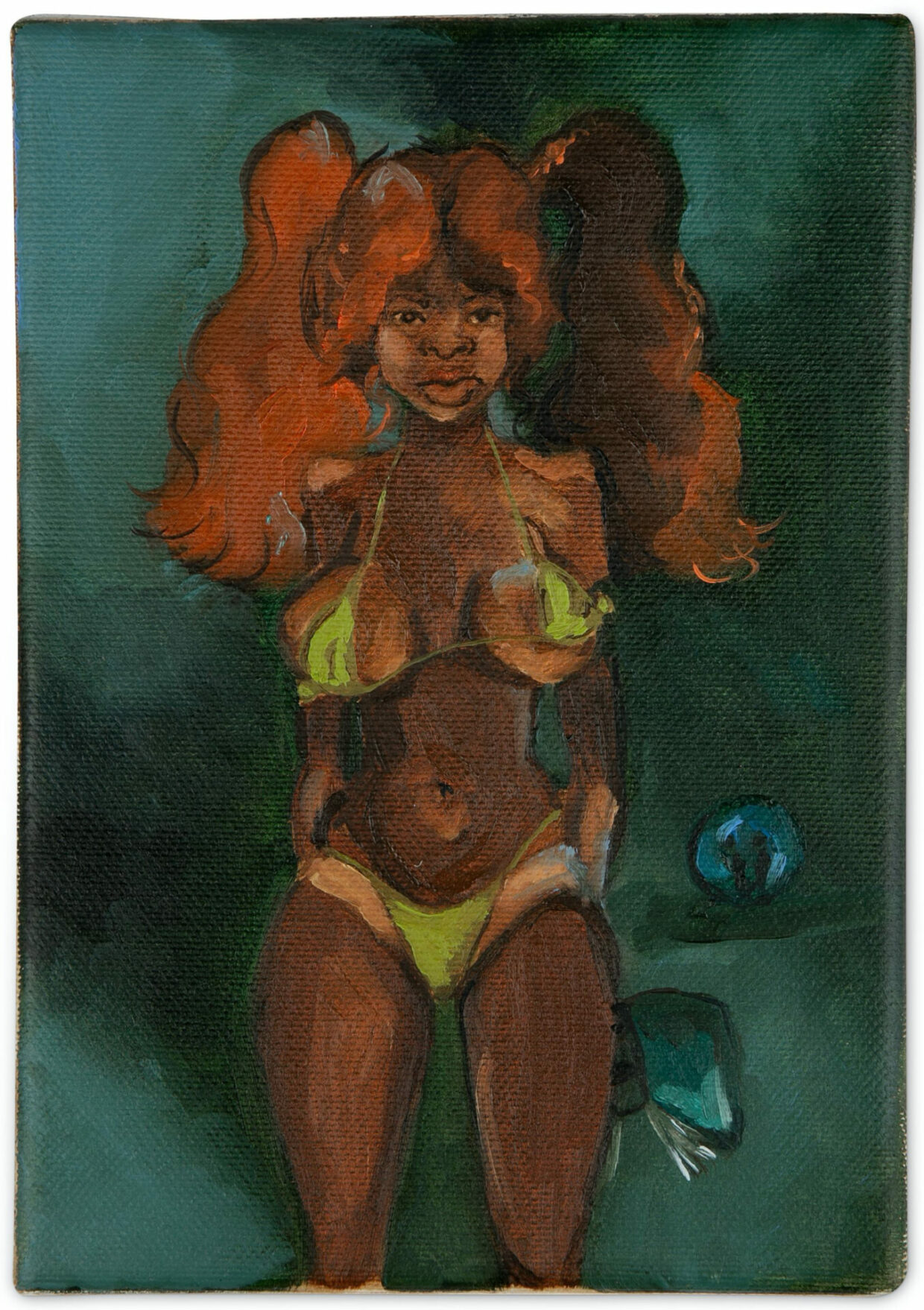

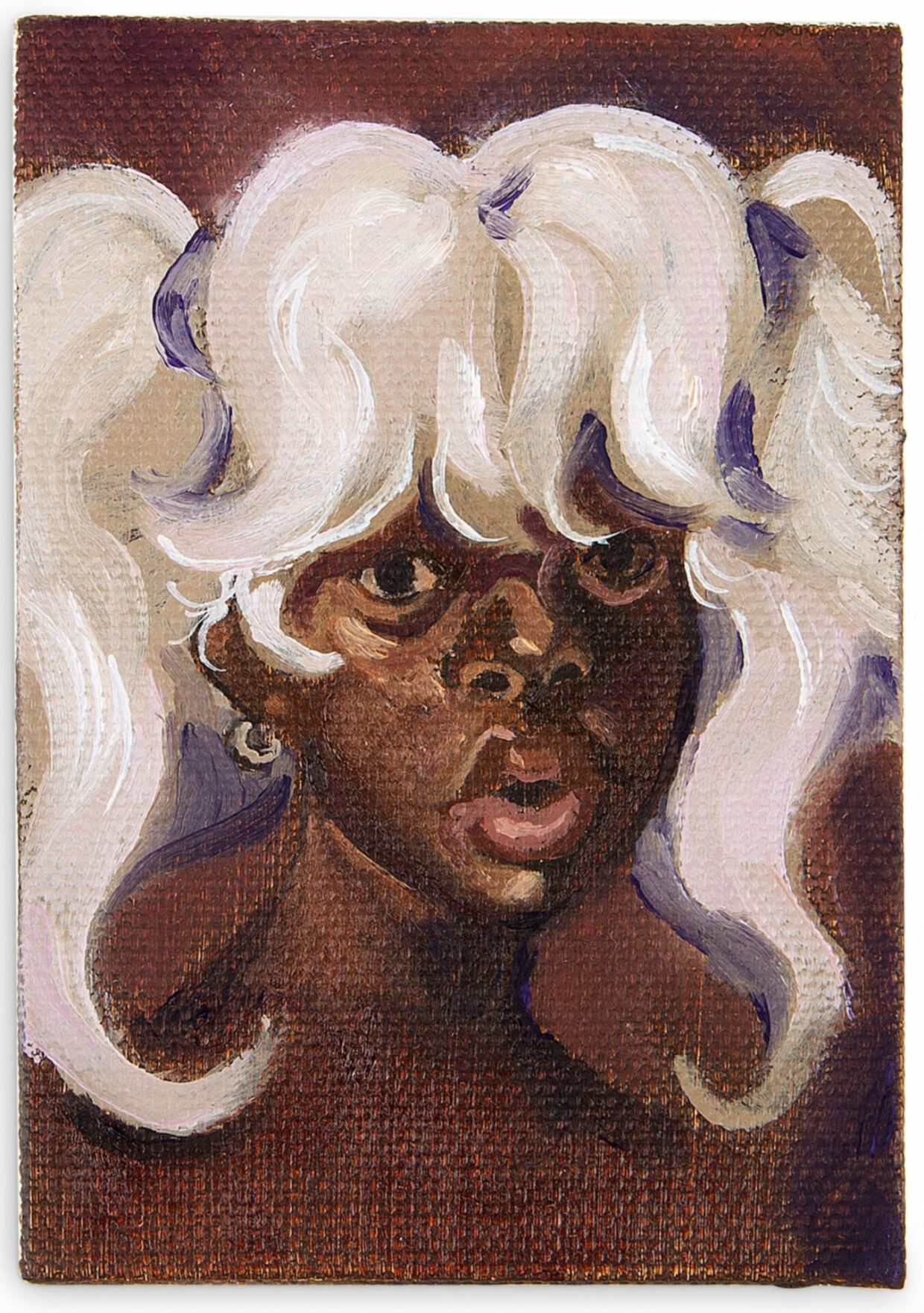

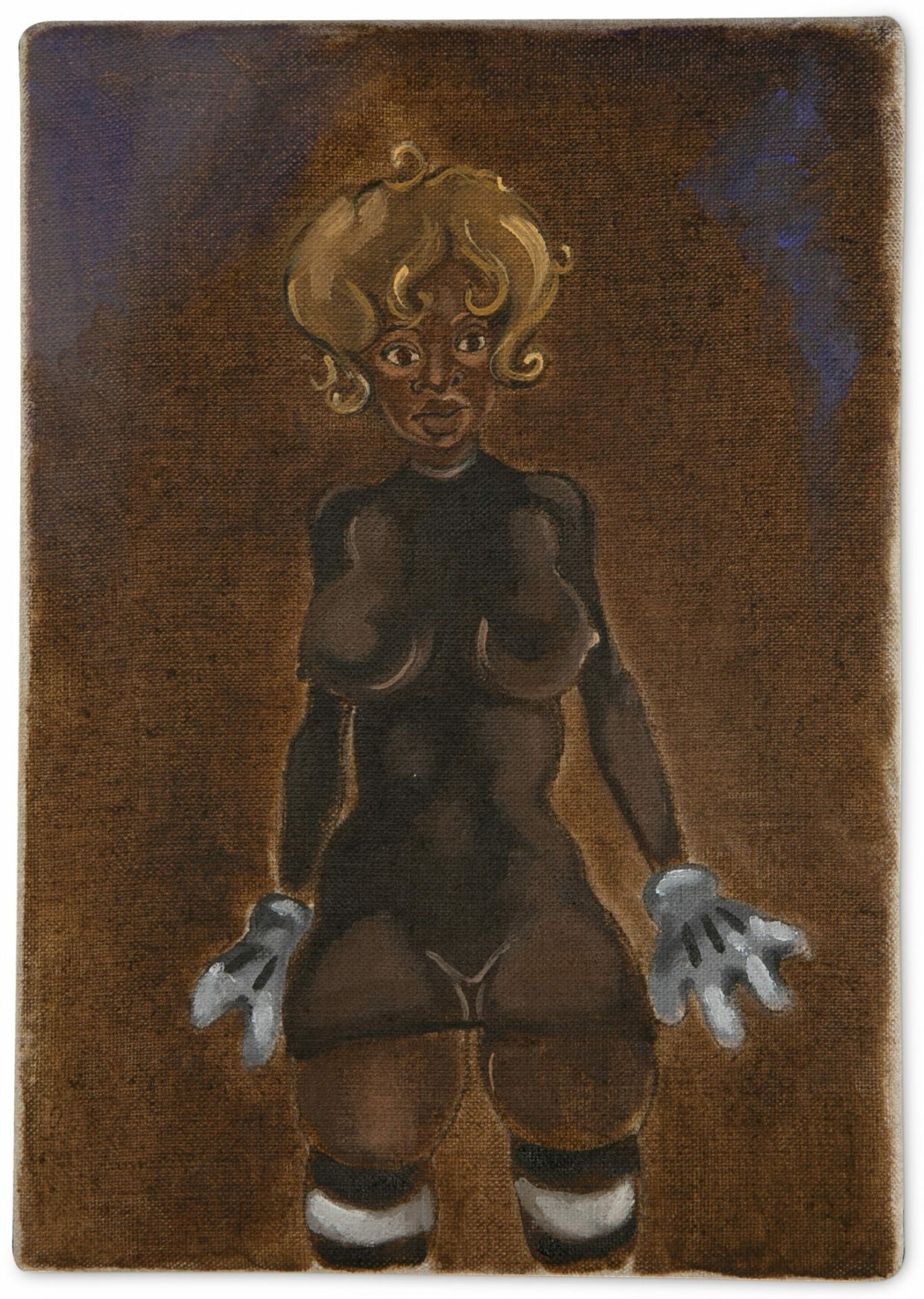

A woman sits in a room, half-naked on a blue velvet chair. She meets your gaze, watches you as you perceive her in her space—were you invited to do so? The painting is titled Figure Holding a Teacup and is one of many portraits by London-based painter Somaya Critchlow, both a traditional nude and something altogether new. There’s a postmodern kink to Critchlow’s paintings—microcosms of deep chiaroscuro that draw the eye to a pastel bouffante of hair, a delicate sweater, or the ripe curve of a bottom or breast.

Her figures resist falling into the category of the archetypal nude—placid, unassuming, white. Instead, the moody umber realm they occupy is one of autonomy. Though an unabashed fan of traditional European painting, Critchlow’s compact canvases are not burdened by history, but inflected with its tropes, crisscrossing centuries and high and low art forms—from Old Masters to reality TV. Critchlow asks: “What is the right way to portray being a woman?”

While she has been classically trained at the University of Brighton and the Royal Drawing School, Critchlow is not seeking to follow blindly in the footsteps of portrait-makers of the past, but reappropriates the technical to challenge our misconceptions about culture, race, identity, and image-making on a fundamental level—working intuitively in correspondence with her imagination. For the fourth and final chapter of SSENSE x Valentino UniqueForm(s), Editor-in-Chief of A Magazine Curated By, Dan Thawley, interviews Somaya Critchlow.

DO YOU HAVE CERTAIN RITUALS IN YOUR APPROACH TO PAINTING?

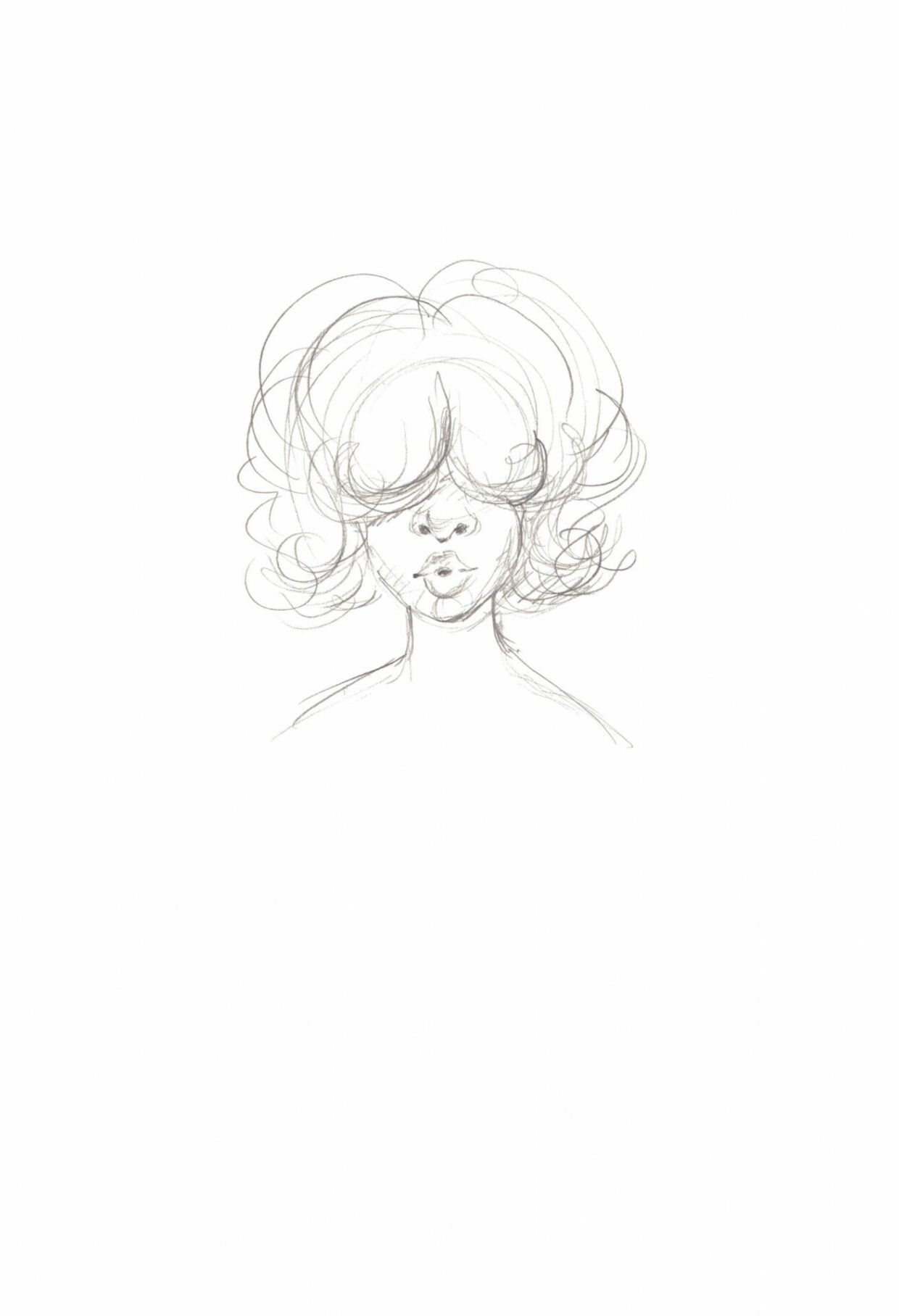

I think the biggest ritual that I have is drawing in my notebook—most of the paintings that I’ve done start with sketching. I don’t like to overthink what I’m doing, I try to let my subconscious be in control. I think that’s my ritual—to sit down and do the sketches and then see what comes out.

WAS PAINTING FROM LIFE SOMETHING THAT YOU WERE INDOCTRINATED WITH AT SCHOOL OR MADE TO DO, OR HAS IT JUST NEVER BEEN SOMETHING THAT HAS COME INTO YOUR PRACTICE?

I had quite a traditional education and definitely painting from life has been part of it. But I always felt like I got quite caught up in the process of painting and drawing, and by having it there from life, it became too much about what I was seeing literally, and not any feeling or much more to it. I went to drawing school so I could study life drawing, and I really wanted to be able to understand how a body works and to know it in a very proper sense, so that I could use that to be quite inventive.

I WAS WONDERING ABOUT LOOKING AT YOUR PAINTINGS INDIVIDUALLY VERSUS LOOKING AT THEM TOGETHER. BUT ARE THERE ANY WORKS THAT YOU WOULD SAY NEED TO BE CONTEXTUALISED BY LOOKING AT THEM AS A GROUP OR AS A SERIES?

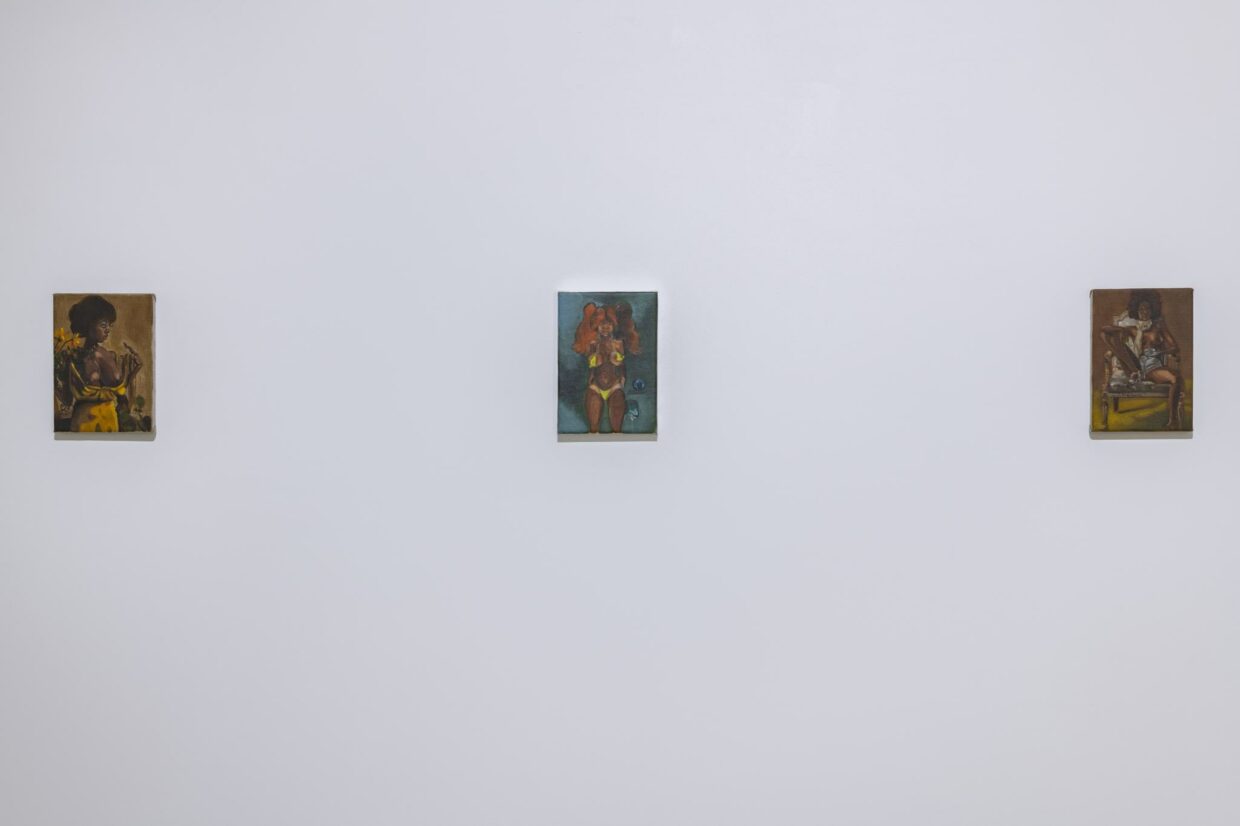

I don’t think they have to be looked at together at all. I think each piece is quite its own thing. I know some people work in series and will have a body of work, which maybe makes sense that they want to show it together. But I don’t really have that. I always think of myself as a bit of a restless painter. You might look at a painting like The Volleyball Intellectual and then Figure with a Teacup and stylistically they’re quite different, but they’re actually quite similar. And that is what I find most interesting to look at—they are speaking two different languages, maybe within paint, yet they’re quite strongly connected. My main concern is just the idea of what good painting is, or what people expect from you and subverting that. Showing the process of painting and how flexible and malleable it is.

IF YOU’RE NOT PAINTING FROM LIFE, AND YOU’RE NOT PAINTING FROM EXACTING BOUNDARIES, WHERE DO SOME OF THESE PAINTED SCENARIOS COME FROM?

A lot of where my characters come from is a strong sense of feeling slightly powerless as a person and how the world has reflected myself back to me. There’s a sense of different characters, or these costumes, or role play. When I was younger I was absolutely obsessed with fashion and Vogue magazine. I had stacks of Vogue and I used to cut them out and make collages with them. I was watching Love and Hip Hop, and that had quite a strong visual impact on me. At the same time, I had been watching Blue Velvet by David Lynch and then had seen a Cardi B music video. And I thought, in a weird way, a lot of these things collide more than you would think they do. I think hip hop and rap music videos are quite a strong reference point, because I find I’m watching these mini-cinematic scenes. I find them quite surreal.

THERE’S A LOT OF POST-MODERN RULE BREAKING GOING ON THERE…

I’d watch something like Blue Velvet and the protagonist would never be a Black woman, but I felt so in touch with the themes and what was going on in those films. So I thought about what happens if you do cross those boundaries. In the same way that I love traditional painting, again, you don’t really tend to see Black people in them. I think maybe more so now because people are getting paintings out that have Black figures in them, but they’ve sort of been in the background, or it’s slightly uncomfortable.

CHAPTER IV

Somaya Critchlow in Conversation with Dan Thawley

A woman sits in a room, half-naked on a blue velvet chair. She meets your gaze, watches you as you perceive her in her space—were you invited to do so? The painting is titled Figure Holding a Teacup and is one of many portraits by London-based painter Somaya Critchlow, both a traditional nude and something altogether new. There’s a postmodern kink to Critchlow’s paintings—microcosms of deep chiaroscuro that draw the eye to a pastel bouffante of hair, a delicate sweater, or the ripe curve of a bottom or breast.

Her figures resist falling into the category of the archetypal nude—placid, unassuming, white. Instead, the moody umber realm they occupy is one of autonomy. Though an unabashed fan of traditional European painting, Critchlow’s compact canvases are not burdened by history, but inflected with its tropes, crisscrossing centuries and high and low art forms—from Old Masters to reality TV. Critchlow asks: “What is the right way to portray being a woman?”

While she has been classically trained at the University of Brighton and the Royal Drawing School, Critchlow is not seeking to follow blindly in the footsteps of portrait-makers of the past, but reappropriates the technical to challenge our misconceptions about culture, race, identity, and image-making on a fundamental level—working intuitively in correspondence with her imagination. For the fourth and final chapter of SSENSE x Valentino UniqueForm(s), Editor-in-Chief of A Magazine Curated By, Dan Thawley, interviews Somaya Critchlow.

DAN THAWLEY

Somaya Critchlow

DO YOU HAVE CERTAIN RITUALS IN YOUR APPROACH TO PAINTING?

I think the biggest ritual that I have is drawing in my notebook—most of the paintings that I’ve done start with sketching. I don’t like to overthink what I’m doing, I try to let my subconscious be in control. I think that’s my ritual—to sit down and do the sketches and then see what comes out.

WAS PAINTING FROM LIFE SOMETHING THAT YOU WERE INDOCTRINATED WITH AT SCHOOL OR MADE TO DO, OR HAS IT JUST NEVER BEEN SOMETHING THAT HAS COME INTO YOUR PRACTICE?

I had quite a traditional education and definitely painting from life has been part of it. But I always felt like I got quite caught up in the process of painting and drawing, and by having it there from life, it became too much about what I was seeing literally, and not any feeling or much more to it. I went to drawing school so I could study life drawing, and I really wanted to be able to understand how a body works and to know it in a very proper sense, so that I could use that to be quite inventive.

I WAS WONDERING ABOUT LOOKING AT YOUR PAINTINGS INDIVIDUALLY VERSUS LOOKING AT THEM TOGETHER. BUT ARE THERE ANY WORKS THAT YOU WOULD SAY NEED TO BE CONTEXTUALISED BY LOOKING AT THEM AS A GROUP OR AS A SERIES?

I don’t think they have to be looked at together at all. I think each piece is quite its own thing. I know some people work in series and will have a body of work, which maybe makes sense that they want to show it together. But I don’t really have that. I always think of myself as a bit of a restless painter. You might look at a painting like The Volleyball Intellectual and then Figure with a Teacup and stylistically they’re quite different, but they’re actually quite similar. And that is what I find most interesting to look at—they are speaking two different languages, maybe within paint, yet they’re quite strongly connected. My main concern is just the idea of what good painting is, or what people expect from you and subverting that. Showing the process of painting and how flexible and malleable it is.

IF YOU’RE NOT PAINTING FROM LIFE, AND YOU’RE NOT PAINTING FROM EXACTING BOUNDARIES, WHERE DO SOME OF THESE PAINTED SCENARIOS COME FROM?

A lot of where my characters come from is a strong sense of feeling slightly powerless as a person and how the world has reflected myself back to me. There’s a sense of different characters, or these costumes, or role play. When I was younger I was absolutely obsessed with fashion and Vogue magazine. I had stacks of Vogue and I used to cut them out and make collages with them. I was watching Love and Hip Hop, and that had quite a strong visual impact on me. At the same time, I had been watching Blue Velvet by David Lynch and then had seen a Cardi B music video. And I thought, in a weird way, a lot of these things collide more than you would think they do. I think hip hop and rap music videos are quite a strong reference point, because I find I’m watching these mini-cinematic scenes. I find them quite surreal.

THERE’S A LOT OF POST-MODERN RULE BREAKING GOING ON THERE…

I’d watch something like Blue Velvet and the protagonist would never be a Black woman, but I felt so in touch with the themes and what was going on in those films. So I thought about what happens if you do cross those boundaries. In the same way that I love traditional painting, again, you don’t really tend to see Black people in them. I think maybe more so now because people are getting paintings out that have Black figures in them, but they’ve sort of been in the background, or it’s slightly uncomfortable.

SPEAKING OF LYNCH AND MORE TRADITIONAL PAINTING, AND THE IDEA OF CHIAROSCURO, WHICH IS VERY STRONG IN YOUR WORK—I WANTED TO ASK YOU ABOUT LIGHTING. WHEN I’M LOOKING AT YOUR WORK, I’M OFTEN LOOKING AT TWILIGHT, I’M LOOKING AT A DUSK AND CANDLELIGHT—DARK SCENES THAT SURROUND THESE LUMINOUS FEMININE CHARACTERS. I’M CURIOUS WHERE THAT SITS SUBCONSCIOUSLY IN THE WORK.

Naturally, I’ve always been drawn to using earthy, dark tones because they just seem more realistic to me. I can see when I look at my work, without having realized, there is a theme of that dusky candlelight that you’re talking about—low-lit environments, even when I’m using brighter colours. The characters at times can be quite fantastical, so I wonder if the lighting is about me wanting to keep it grounded and a bit gritty. I don’t want you to feel like you’re watching a fantasy explosion—it’s meant to have some sort of resonance with real emotions and feelings.

LOOKING AT THE WAY YOU IMPLEMENT LIGHT, IT’S OFTEN IN THE INCREDIBLE COLOURED HAIR OR THE COSTUME. A SYNTHETIC ELEMENT THAT COMES THROUGH IN THE ORNAMENTS AND THE EMBELLISHMENT OF THE WOMAN, MORE SO THAN THROUGH HER SURROUNDINGS.

I think that’s because I love traditional paintings, they have a similar tone that I probably have taken in subconsciously. At the same time, we’re living in the contemporary world where there is a lot of bright colour. And while painters didn’t have access to synthetic oil colors in the past, we do now. So it is interesting to blend the two. I think when you’re painting, you are painting light no matter what you are painting. When I went to Italy on a residency at Palazzo Monti in Brescia, the lighting there was so different, and it really threw me how dim it was because it was this big old building. It had quite a profound impact on the paintings—painting them low-lit in a low-lit environment.

YOU MENTIONED EARLIER THAT YOU’VE BEEN INTERESTED IN FASHION AND IT’S SOMETHING THAT HAS INSPIRED YOU IN THE PAST—HOW DO YOU CLOTHE YOUR SUBJECTS?

I’ve got a quite strong sense of style, I remember someone asked me to send a little moodboard over of what I like to wear and they said, “Oh, you’re the very avant garde one.” I was always really obsessed with the occult and witches when I was younger and now it’s probably more looking at clothes and how they fall off the figure. Like with the Harlequin painting, it’s such a beautiful kind of pattern to paint and that’s really exciting to work with on a painterly level. And then one of the other women in another painting is in a pink bodysuit, that was inspired by Nicki Minaj. When I paint I choose the clothes that I like, and they are kind of avant garde. I quite like Victorian and Edwardian dress, and maybe I’ll use that as a kind of starting point.

I WANTED TO ASK YOU ABOUT SCALE, BECAUSE YOU HAVE DEFINITELY PLAYED WITH THE MINIATURE. HOW DO YOU NAVIGATE THAT AS A YOUNG PAINTER? YOU’RE STILL SORT OF EXPERIMENTING WITH SO MANY THINGS.

I began doing preliminary drawings and then actually working on a small scale because I went to the National Gallery with my grandfather when I was younger and we’d discuss how the old masters made a small painting, a study, for a much bigger painting. Because I was initially working mainly from my imagination, it was sort of a way to work it all out. And obviously a small scale painting is far more forgiving. You know, you do it wrong, you just paint the thing out and you go again. Then I realized that I wasn’t really making studies. These were paintings that were finished and done. There’s a thing around painting big, and how that’s the “right way” to progress. But stumbling on this really small scale I do think part of it is a bit of a control thing. It’s quite a dominating experience. You’ve got this small thing and it’s also very delicate. I love the tiny brushes.

I think actually the main thing about painting small is the subject matter, maybe there’s a timidness to it as well, because the subject matter is such a strong thing. I never think it’s just frustrating that inadvertently, by just being a Black woman, it’s political.

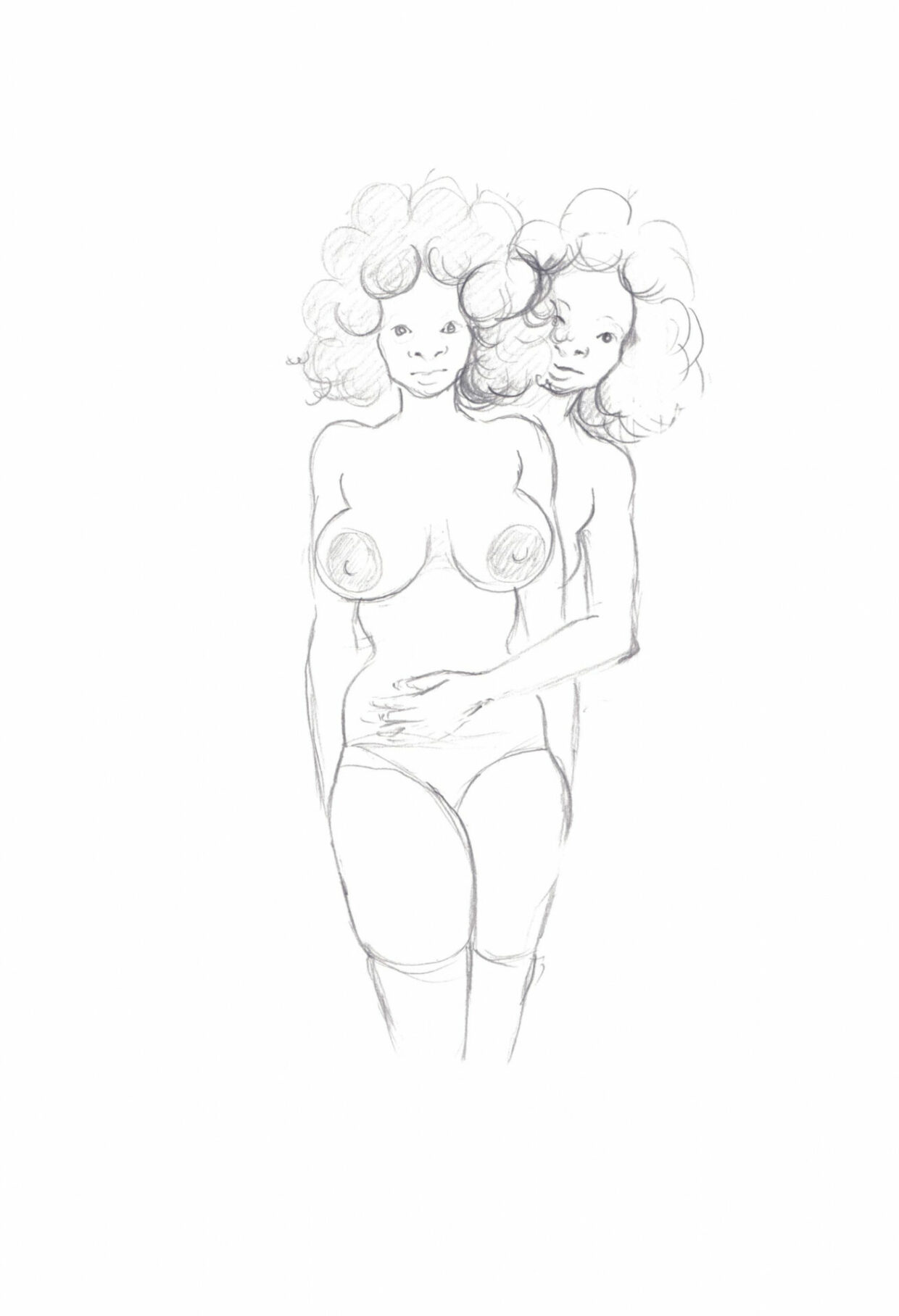

THERE ARE OBVIOUSLY RECURRING LEITMOTIFS—THE HAIR, THE BARE BREASTS. I WANTED MAYBE TO HEAR YOUR POINT OF VIEW ON PORTRAYING THOSE ELEMENTS AGAINST DARK BACKGROUNDS AND SCENARIOS, TO ACCENTUATE FEMININITY IN THAT WAY.

I’ve always maintained that I have had a fascination with hair as a Black woman because it’s such a touchy subject—good and bad hair. And I have gone through periods of relaxing my hair and then having natural hair—it’s just always been a big thing. And then when I was looking at Love and Hip Hop and watching music videos from Nicki Minaj and Lil Kim, the hair is just incredible in the same way that it is in fashion, you can manipulate it to say so much about a character. Think of how Jackie Kennedy would have worn her hair. It’s a whole part of her oeuvre and character and how we read her. I’ve never had simple hair—it’s either huge or I’ve slicked it back… I don’t just have hair that falls like that—it’s a big part of who I am and I’m really conscious of it. So I think I project that onto my characters. When I’m painting hair, it’s got to sit right.

And then with the breasts, I just think being a painter and being taken seriously and doing life drawing—the majority being of nude women—there’s something about it that was a bit of a fuck you. I’m just going to blow this up as big and silly as I can, and make it a serious painting. And what can you say to me about that?

When I was coming towards the end of my postgraduate, I had found my way a bit with this body of work. And I remember a tutor coming in and looking at it and then I had a life drawing class with her and she was like, “Oh, your breasts are too big, you know?” But I didn’t think so. I was just drawing what I see. I think that with femininity you can’t get it right. I was asked, “Are you not going to paint women living real experiences?” And I was like, what does that even mean? There are so many different experiences. Does it need to be some sort of limp head, small breasts? What are we trying to argue is the right way to portray being a woman? Hair and boobs and sexuality have a lot to do with shame because part of it is how other people are viewing you, rather than how you’re viewing yourself. And I think by being playful with that or being aggressive in a way, though I don’t find it that aggressive, creates your own language within paintings.

It was quite a freeing experience to take life drawing out of life drawing context and just sort of strip everything down, and then be in control of the boundaries and not have them dictated to me by art history or by the world.

Source: SSENSE