Maripol, godmother of instant photography, on the serendipitous magic of Polaroids

Nov. 19, 2019

By: Maraya Fisher

“Remember to relax,” Maripol said as I stared down the barrel of her Polaroid camera. To be in front of her lens is to occupy the same space, the same focus point as countless downtown, New York icons, from Debbie Harry to Madonna, Andy Warhol to Jean-Michel Basquiat. As someone who is nervous in front of any camera, I certainly needed the reminder. I exhaled. “Good,” she said, taking the shot. She dropped the newborn image into the open jaws of a Moleskine held by her assistant, who immediately snapped it shut.

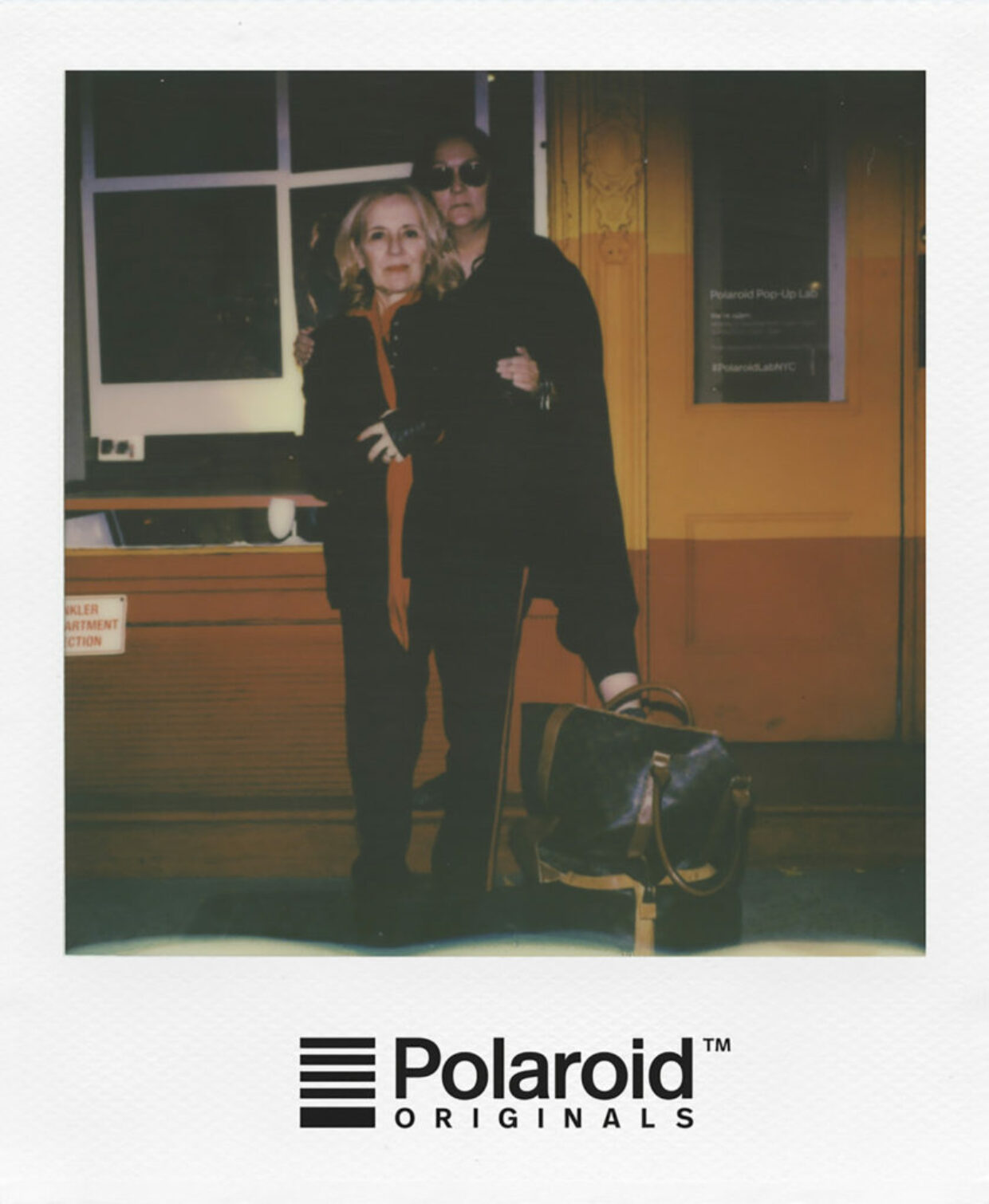

I was ushered back into the rainbow Polaroid Pop-Up Lab in SoHo to witness a conversation between jewelry designer, former Fiorucci art director, and “gatekeeper of ‘80s club culture” Maripol and PR queen (and formidable America’s Next Top Model judge) Kelly Cutrone. The discussion kicked off a series of events supporting Polaroid Original’s latest release: the Polaroid lab, which instantly prints Polaroids, on the signature film, from your phone.

During the following hour, I felt I was a voyeur during an intimate downtown family reunion. As Maripol clicked through a slideshow of her Polaroid collection, Cutrone and the audience members who formed the first few rows—including the legendary Studio 54 photographer Rose Hartman, who showed me her creased photo of Bianca Jagger riding a white horse from her wallet upon introducing herself; Adriana Kaegi of Kid Creole and the Coconuts; and curator and cultural critic Carlo McCormick—yelled out the names of those they recognized: Anna Sui, Grace Jones, Keith Haring, Fred Schneider, Debbie, Andy, Madonna in a pink wig. Maripol gave the story behind each snap and Cutrone provided the cultural context and significance for the audience members who never partied at the Mudd Club.

There was a lively debate between Cutrone and the audience over how Andy Warhol foresaw the influencer age with his (disputed) 15-minutes-of-fame quote that ended with the French woman behind me passionately comparing Warhol’s oracular genius to Manet’s. When Maripol clicked to an image of the artist Ronnie Cutrone, Cutrone warmly recounted her first few dates with her late ex-husband, which involved her following five feet behind him with a leather dog collar around her neck. Maripol laughed as she recalled the time she left her boyfriend, Edo Bertoglio, in New York to travel across the country with the punk band The Screamers, with the job of sitting shotgun to ensure the driver wouldn’t fall asleep.

In the chaos of the conversation’s aftermath, Maripol slipped my Polaroid into my notebook. “You can look at it later!” She said, returning to a crowd of dear friends.

Prior to her discussion with Kelly Cutrone, I spoke with Maripol about her obsession with Polaroid, the time her Harley was stolen at the Mudd Club, and the Instagram age.

Maraya Fisher—I was reading Maripol: Little Red Riding Hood, and I saw that you were gifted your first Polaroid camera in ’77. Why did you stick with Polaroid as opposed to trying other cameras?

Maripol—Actually, when I did the Beaux-Arts school in France, the first year you do a bit of everything. So I was taking photography, I took architecture, and I was drawing live models nude, and painting class, and movies and this and that. Then when we came to New York, it was only for three months in ‘76. On Christmas ‘77 Edo gave me my first SX-70, brown leather-clad. He was a photographer and he was running to Duggal back then. He was shooting analog so he had contact sheets, and it was complicated and costly. Me, I found a place in Canal Street which was selling the prints [Polaroid film] for not that much, and it became my tool, like your iPhone is your tool, in whatever I was doing, whether it was styling or costuming. You know, being in New York was magic. So if you go on the top of the Rockefeller Center, what are you going to do? Take a picture of the Empire State Building in front of you. It’s an amazing tool to shoot your life. I always say that my art was my life, but my life became my art.

Maraya—I think of your Polaroids as a very intimate look at a certain glamorous, dirty, iconic era of downtown NYC. When you were taking photos, did you see yourself as simply capturing your nights with friends or did you think of it as something greater, like archiving a time in New York City history? Did you sense, in the moment, how special the time you were living through and documenting was?

Maripol—I think I was in the moment. I never calculated that eventually they could be precious because they witnessed a time. It’s part of my art that I always come out with projects, like, 20 years after. I have a bunch of other pictures, but I’ve never shown them. It’s the same with Downtown 81, which just got released at Metrograph. It was not really calculated; it was just an instant moment, a magic moment.

Maraya—This time is romanticized; as someone who was drawn to New York City, I was looking at this era. CBGB and Studio 54 and all of that. Could you allow me to live vicariously through you and walk me through a typical night out? How did it start?

Maripol—Yes. So, typical night out; first, it’s about how you’re going to portray yourself. Back then we wore a lot of vintage, so I made my clothes because I never found anything. You have to realize that the couture houses as we know them now, even Gucci or Chanel, were catering to Madison Avenue old ladies who had money to afford the clothes. I was working at Fiorucci, so I was lucky to get stuff, but I also made clothes for them [Fiorucci] and jewelry. That was also my passion. I consider these objects almost like sculpture now.

But basically, yes, so we got dressed. We had a motorcycle so we would go easily from uptown, because we lived on 79th. We had a Harley and we would go all the way to the Mudd Club. We were known to be the bikers, definitely, until the bike got stolen from the Mudd Club. Not good. Well, that’s because my boyfriend didn’t shut it off. It was not pleasant.

Anyway, makeup was very important, hair was very important, but it was in a natural way. One time somebody said to me, ‘How long does it take for you to get dressed like this in the morning?’ I said, ‘It takes me as long as it takes you to get dressed in the morning.’ So I think it’s a question of style; people assume that because we were so dressed— or, underdressed, by the way—that it would take us so long. It was just like, ‘Alright, I’m just going to wear a scarf around my breasts. I was famous for being nonconformist, French with taboo. I was arrested a couple of times on the beach in Long Island for wearing no bra. I thought, ‘What is this country about?’ I mean come on, please.

Maraya—You got arrested, tell me more about that!

Maripol—I would just get arrested. One time I avoided it; this woman came to me and said, ‘You can’t be like that; I’m going to call the cops!’ By the time the cops came back, of course, I put my stuff on, I said, ‘Yes officer what’s the problem?’

Maraya—So Mudd Club was your spot of choice?

Maripol—Well, yeah, we didn’t live too far. Mudd Club was opened by Steve Mass, who had some ambulance company in New Jersey. He was a cokehead. But then Anya Phillips, who was the wife of James Chance, and Diego Cortez, they had created a movement called no wave. No wave was beyond new wave. It was like nihilism. A bit like, you know, anti-everything.

That was toward the end of Studio 54 and sometimes people from Studio 54 went [to Mudd Club]. Everybody went there. We saw Mick Jagger. But then we had bands. I saw the B-52s play the first time they ever played. Basquiat had a band called Gray who played there. So many people played. Music then was pretty interesting because we already had the invasion of the English music, we were not far from the ‘60s, so it was a lot of Motown—not that much rock. I would say that it was new wave and the first emerging of hip-hop, people like Fab 5 Freddy would bring elements from the Bronx. I’m talking pre-MTV. Then there were artists, like Futura and Keith Haring, working at the Mudd Club. It was basically our living room. The days were really pretty much non-existent because we would be sleeping.

Maraya—That’s amazing. I guess we can bring things to the present. What do you think of the advent of the camera phone and Instagram and how people sort of have access to document their lives in such excess.

Maripol—Yeah, it could become annoying. I kind of quit Facebook, because I thought it was for old people. I consider myself young at heart. But Instagram was really exciting at the beginning, and I think it was a great tool to find for photographers. But now, of course, everything becomes commercial, and you’re bombarded with all these ads, all these labels, all the time. Then it becomes boring; again, Facebook: people showing their cat, the food they eat. I can’t, come on, please. I have a tendency to do the same, then I’m like, ‘Wait a minute, no, no, no.’

Maraya—What excites you about fashion, art, and music these days?

Maripol—All of those. I went to see [Yayoi] Kusama yesterday. I’m so inspired by women like her. She’s, what, 84 years old? And she still does work; it’s like Louise Bourgeois. There this sense of women artists being discovered, which is kind of weird. It’s almost an offense. Regina Bogat is 89 years old and they are just discovering her. Nobody really knew the story, but she was married to Alfred Jenson, who was a big artist in the ‘50s, ‘60s, ‘70s. She lived in his shadow, but she never stopped working. My generation became more independent and probably your generation is becoming more and more independent. So yes, I’m inspired by everything, and I said something mean about [Instagramming] food but I’m a foodie. There is always gonna be a new chef and new writer and new filmmaker, and there’s always something to discover.

Source: Document Journal