GREG LAUREN’S SCRAPS BELONG IN A MUSEUM

Jan. 26, 2021

By: Heather Snowden

Trying to boil Greg Lauren’s brand down to one word is like playing a puzzle — the kind of puzzle you pore over for hours, trying to find the right piece because there are so many that could fit. You get heritage, memory, identity, consciousness, luxury, upcycled, trash, Americana, military, vintage, all bouncing around in your head simultaneously, but none work in isolation, they don’t quite do the label justice. But they do if you put them all together.

Word games are child’s play compared to the problem-solving that goes into Greg Lauren’s collections. At first glance, his work could be interpreted as that of yet another luxury fashion house which markets itself as green simply by upcycling second-hand gear and whacking on a wild price tag. And while that surface-level analysis isn’t necessarily wrong, it does a massive disservice to the web of nuance that operates beneath surface. Here, every millimeter of fabric addresses an issue, serves not one but multiple functions, and has many stories to tell.

That has never been more true than within the “3N1” series, which is a key part of his Fall/Winter 2021 collection. Firstly, every piece in this capsule can be used in more ways than one; a parka coat turns into a flight jacket turns into a utility bag. As per Lauren’s signature style, all of it is created from vintage military fabrics — old army tents and garments. Secondly, it is the first range to launch under the new GL Stitchwork initiative, meaning the 3N1 pieces are made only from the stitched-together scraps leftover from a previous collection (that was also made from the scraps left over from previous collections). It’s like scrap Inception, and like the movie, to fully understand the bigger picture, you need to go right back to the start.

Greg Lauren is Ralph Lauren’s nephew. His father, Jerry Lauren, was the head of men’s design at Ralph Lauren for 50 years. He was born into the brand empire in 1970, and from that point on, the concepts of identity and clothing were intertwined. “Everything was seen through the lens of style,” he tells me over Zoom from his Los Angeles atelier earlier this week, “even if we were talking about politics. Growing up that way, I was exposed to this incredible visual education in a version of style that was tied directly to something that was happening in the world around us.”

“I was exposed to vintage clothing at a very early age, too — we’re talking seven or eight years old,” he continues. “I learned to pick out pieces that I knew meant something; a beautiful faded army shirt or a US Navy jumper. I knew how to spot the ones that had the best patches, or the ones from a certain era that meant they were made from cotton, not synthetics. I wore all these pieces. None of my friends understood. I always talked about how I had these great, faded Cub Scout shirts, but nobody ever said to me, ‘Do you want to be a Cub Scout?’ No-one ever said, ‘Do you want to learn how to do the things that the patches actually stand for? Do you want to learn how to build a fire?’ I had absolutely no understanding of what any of it meant, or the actual history of it. But I knew they meant something.”

That context gap was something he had to reckon with later in life. “I knew that Ernest Hemingway had incredible style, for example, before I had any idea that he was a writer. When I first was exposed to his first novel, I was like, ‘I know that guy. I’ve seen that portrait. He’s so cool. He’s got great style.’ I learned about JFK’s Paul Stuart suits and his Ray-Bans before I learned about him.”

Of course, once his contextual understanding started to grow, the questions grew with it: “As I got older, I started to ask things like, ‘Wait, who are we individually? What does tailoring even mean? We don’t need to wear suits — there’re no longer dress codes that require it — but what does a suit mean?'” These queries were paired with the development of his personal taste, too. It shifted away from the formality of his inherited heroes like Cary Grant and moved towards flawed characters like Colonel Steve Austin and Mad Max. (Tellingly, one of his first collections was titled “Destroying Cary Grant.” On that, he explains: “I needed to destroy the idea of [inherited heroes] to find my voice. And so that included just literally destroying tailored pieces that Cary Grant might’ve worn.”)

“I was always drawn to the less glamorous pieces. Not the officers’ clothing, not the glamorous flight jacket with the white scarf blowing in the wind like in the movies. I’m from the era of [Vietnam war movies like] Platoon. I was trying to make sense of the previous generation, of the things that were going on in the world. I was also obsessed with this idea of ‘Why do we want to look and feel like a soldier without actually being one? What is that? What is our connection to that? And is it fair? Is it okay that we can own someone else’s story by owning a piece that they wore?’ That really perplexed me, this idea of feeling entitled to the story and soul of the piece.”

When you stick a pin in those questions for a second, you start to get a real sense of the ethos the Greg Lauren brand is built on — a foundation of bringing together stories and histories in a way that is celebratory and considerate. The more research he started to do from this point on, the more fundamental that ethos became.

Part of that research involved earning the right to these stories. In his view, the way to do that was to head to LA’s Rose Bowl Flea Market at bonkers o’clock in the morning and physically search for the perfect piece. Missions like these would eventually unveil treasures, like the time he found a dusty mountain of US Army duffle bags and tents. “I started climbing it, like a kid. I would pull them out, one-by-one. When I got back to my studio, I started deconstructing them.”

The deconstruction process was when he got his ah-ha moment. As he started to take the tents and duffle bags apart, Lauren found so many “little notes, little writings, and patches, and personalization. It meant something to me, and then I started to imagine, ‘Oh, god. Is this a note that didn’t get to someone? Or, what is this little thing?'” He realized that these notes and curiosities made the concept of sharing histories tangible and by returning them to a functional state, he was adding his own tale into the mix, too. And the more he started to understand these concepts and break them down further, the more intricately they influenced elements of the design process.

Take this US military gear as a concept, for example. At some point, while you’re brainstorming the many things it represents, you will touch on the word Americana. But then, what does Americana mean? By definition, it means “materials concerning or characteristics of America, its civilization, or its culture,” but what are those materials? Other than the army fabrics? As Lauren descended down this semantic rabbit hole, he arrived at the quilt — an object that, in its essence, is combined histories and experiences stitched together by someone making something new — and from there he discovered Trench Art.

More specifically, he discovered the centuries-old tradition of military quilting, of the incredible intricate textiles stitched by soldiers during war. “I thought to myself, ‘This is incredible. These are things that these soldiers did.’ These were men, soldiers that embody old-fashioned, masculine stereotypes, who, in their moments of vulnerability, in their moments of fear, are quilting and stitching. They’re doing needlework. It was really, really profound to me. I felt like there was a direct connection to my team and I, hundreds of years later, who are using the scraps of repurposed military fabrics, turning those elements into beautifully tailored garments, into unique spins on archetypes.

“Quilting is a really important thing for me. I’ve been doing that for a few seasons. Spring ’21 was called ‘Deconstructing Americana.’ We did a lot of pieces in that collection that were intentionally referencing 18th-century quilt work and the work of a community called “Gee’s Bend” [a small, remote, Black community in Alabama with a tradition of quiltmaking that dates back to the 19th century. As an initial contribution to Gee’s Bend, the brand committed to donate all net profits from the sale of each piece that referenced their work back into the community.] “We’ve also worked with local quilt makers here in LA to actually use our scraps to create beautiful quilt patterns. I really wanted to address quilting as an art form, but also the responsibility of designers to be more accountable for where our inspirations come from.”

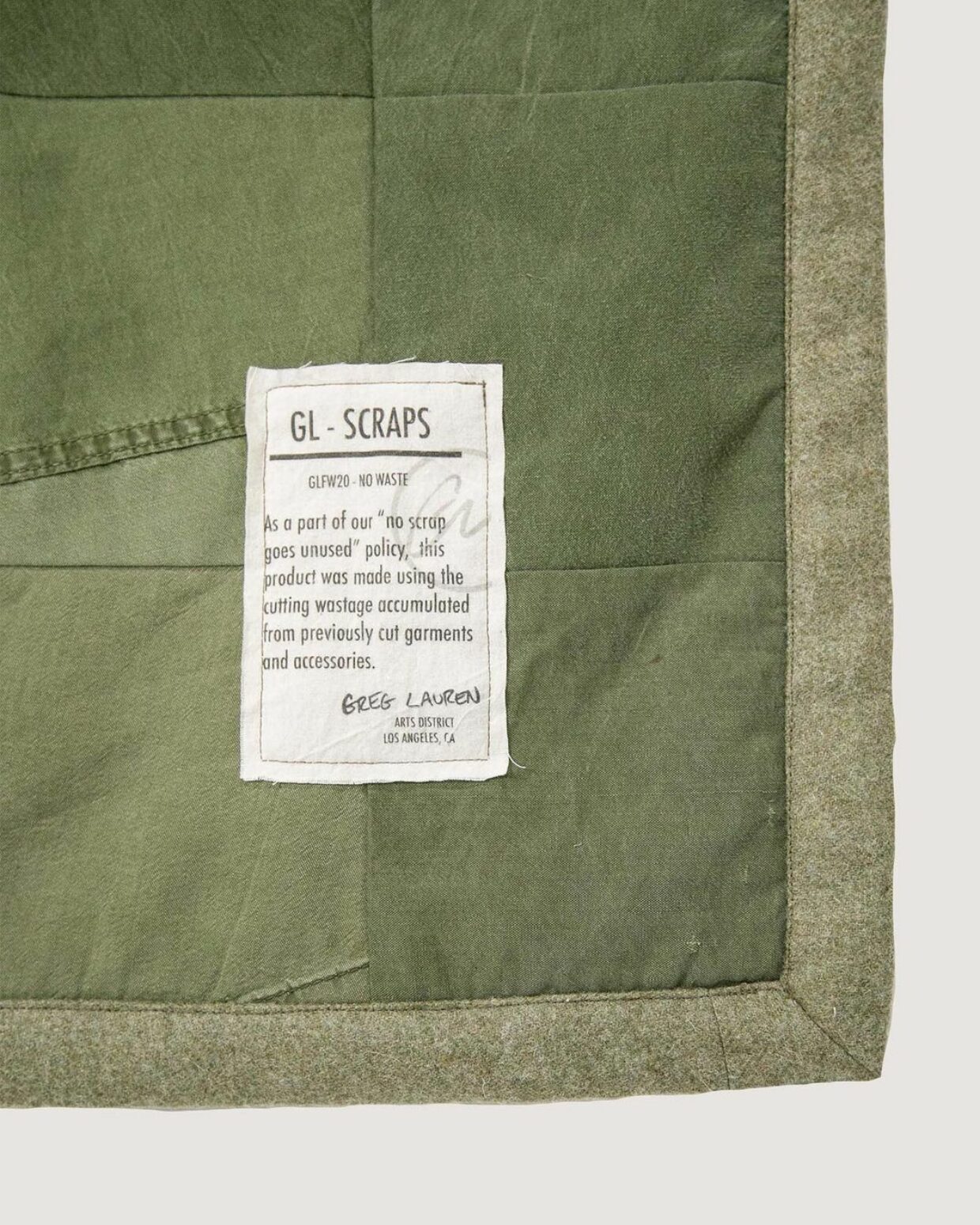

In 2020, Lauren launched the GL Scraps initiative, a project in which he challenged himself and his team to repurpose scraps left over from previous collections and transform them into garments. “The process takes all of the scraps and cuts them into six-inch squares that will be stitched together in a classic, grid-like quilt; You see this sea of colors and details and hardware, that were all part of the original pieces.” The side effect of cutting all of those scraps into a specific shape, however, was that a load more scraps were created as a consequence.

“I really do have this ‘No Scrap Goes Unused’ policy. I’ve been saying that from day one. I would go by one of my cutter’s tables and literally pull something out of the trash and say, ‘What are you doing? This is an amazing pocket flap.’ I could see the transformation just by holding it.” But when you cut down scrap after scrap after scrap, at some point, you’re left with “a certain batch of scraps that are perplexing because they’re either too small to use or they’re really irregularly shaped and you kind of wonder, ‘Wow, how am I going to use that?'”

“That was the catalyst for the GL Stitchwork Program. It is an extension of GL Scrapwork. We’ve explored so many different processes, but this one is the most authentic to what we do at the studio. We literally took all of those remaining scraps and stitched them down in a basic, simple stitch pattern that is reminiscent of when I first learned to sew on my mother’s ’70s Singer machine. [At the beginning] I repaired things with a very basic, almost sketch-like stitch pattern that was really a back-and-forth zigzag. The stitch-work process that we came up with now, which is much more efficient and organized, references that.”

Lauren continues: “It’s a very simple approach, but the materials we work with say so much, they bring so many different elements. And it was a lot of fun pouring out bins of scraps onto a table. For me, it’s like putting paints on the table, then bringing the paper in. I start to see things immediately. That’s the beauty of it. I don’t see a sea of scraps. I don’t even really see scraps. I see potential. I see the transformation. I see colors. I see the whole piece, and then I see details. And even though these scraps might be from similar color or a similar world, each one has a different story. When they come together, it’s beautiful.”

The “3N1” series is yet a further extension of this eternal quest for reuse and function. “I had this idea: what if the pieces that we make could be used in more ways than one? What if you could get more out of it? What if the person who owns one piece could actually find two or three or four more functions out of it? What if that cold weather parka could transform into something wearable when the weather changes? What if it could give me something else? All that came from staring at the pieces themselves. It’s no different than when I look at scraps or a vintage garment and I see something completely different.”

He hopes that difference could become a template for other brands that are looking to implement responsible production practices but don’t have the economic resources to play with.”I try to shed light on what is possible so that we can actually experiment. We can introduce ideas that most people don’t know about and that most companies can’t do because they’re not cost-effective, they’re not realistic. We’ve got to keep pushing the needle in terms of being creative and innovative and having our ideas that we have as artists [in order to] support the sustainability initiative. It’s our responsibility to keep pushing the envelope to go further and further to make these things more cost-effective, more available, more accessible. And that’s the long-term goal: Without compromising the creativity, to make these things that we create more accessible.”

“Making things responsibly is one of our main pillars of the Greg Lauren mission statement,” Lauren concludes. “Everything gets put through that lens. But there’s nothing that I love more than a creative problem to solve. If there’s a way to find a solution creatively, I love it. I think that’s exciting.”

Source: Highsnobiety