As Long As You’re Stuck in Your Apartment, Give Yourself a Story to Live

May. 21, 2020

By Wendy Goodman

I don’t mind being alone. I like it,” says artist Peter McGough from his West Village apartment, where he is quarantined along with his dog, Queenie. “I have my books. I have all sorts of things to keep me occupied.”

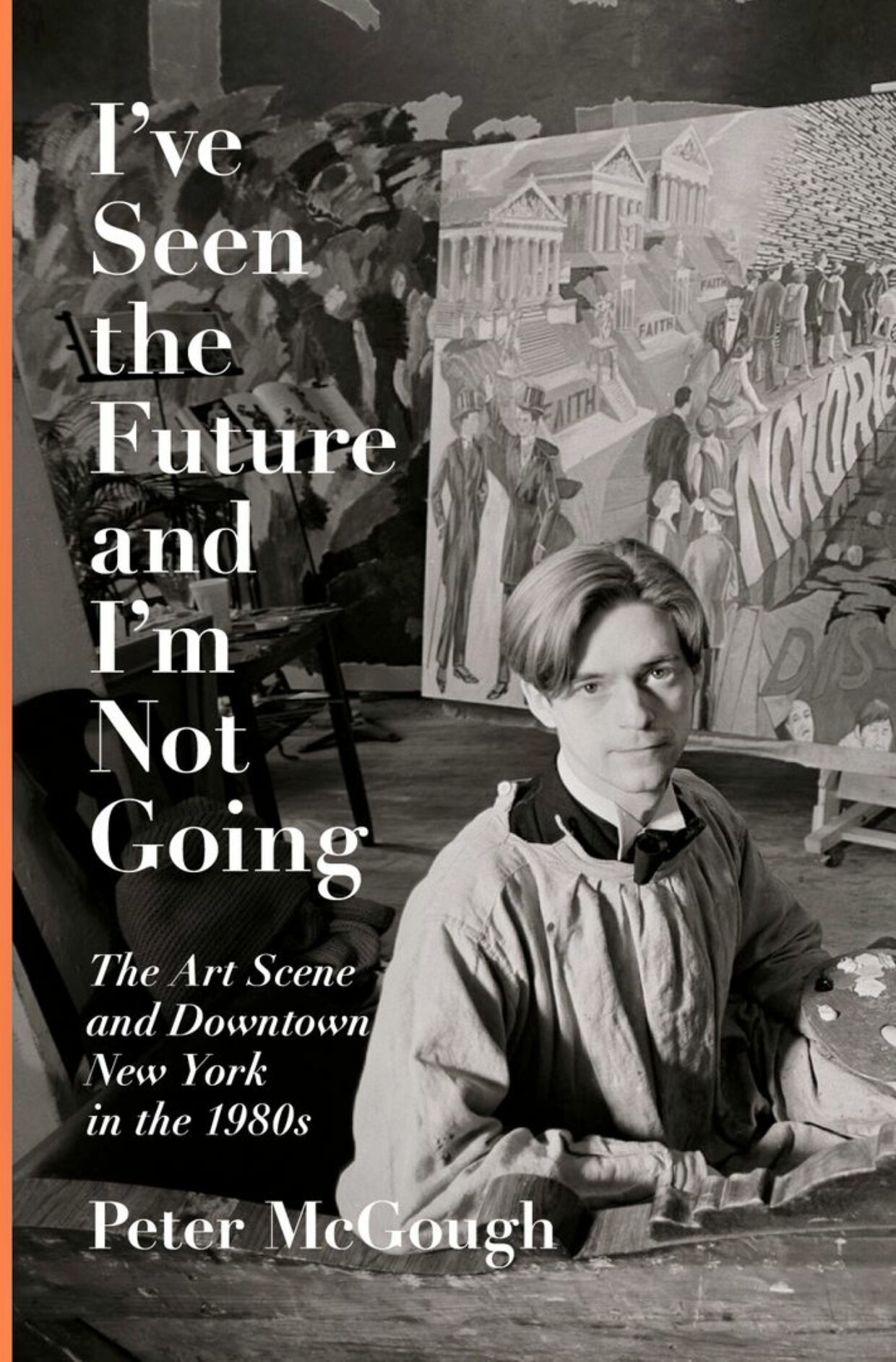

This past fall, he published a memoir, I’ve Seen the Future and I’m Not Going: The Art Scene and Downtown New York in the 1980s, mostly about his years making art — constructing and then dogmatically living in an entirely Victorian-style world — with David McDermott, his onetime lover and art-making partner. The two dressed as if they were in a period film — top hats, detachable collars — and even puttered around the city in a Model T. Their work appeared in three Whitney Biennials and was exhibited by Cheim & Read in New York, Galerie Jerome de Noirmont in Paris, and Bruno Bischofberger in Zurich, and they made the covers of Artforum and Art in America. All the while, they lived in an extraordinary manner, whether it was in their 1840s townhouse on Avenue C, lit by candles and heated with wood-burning stoves, or in the 1865 Kings County Savings Bank at the base of the Williamsburg Bridge, or in their 1790 house in the Catskills. It was all grand in a Miss Havisham kind of way. “Even when we lived in a hovel,” McGough says, “we’d get a can of paint and paint it. I found 18th-century furniture in the garbage! I found velvet chairs from the ’40s. People threw out so many good things.” Nonetheless, they made a great deal of money, overspent lavishly, then lost much of what was left to back taxes. McDermott moved to Ireland. McGough joined him for a spell, then returned.

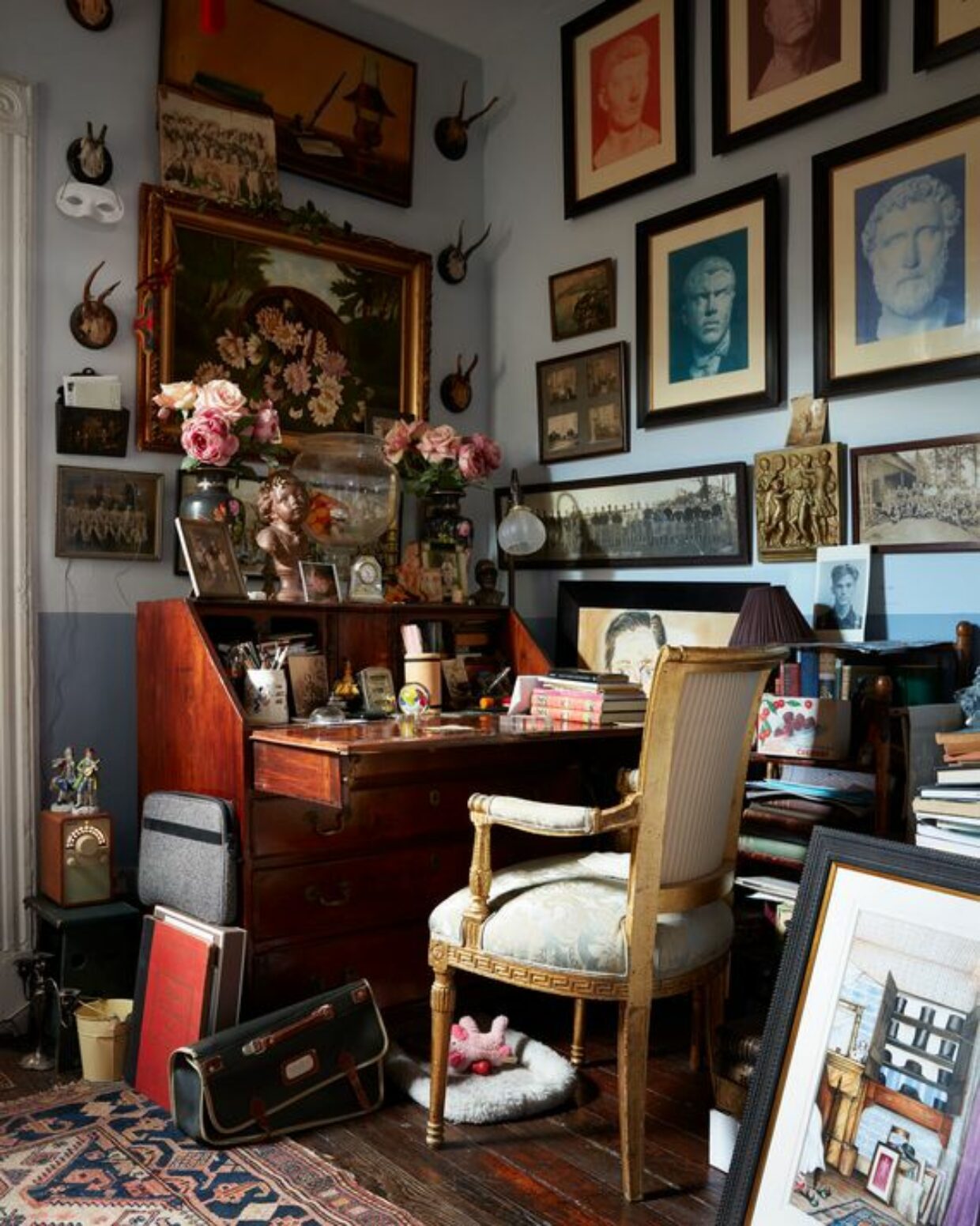

He moved to this apartment three years ago from a 1930s building on Christopher Street. His friend Fernando Santangelo, the interior designer, had been living here (“It was all white, and it was sparsely furnished with beautiful things,” McGough says), and when Santangelo moved out, McGough moved in. It’s the only apartment in the building that hasn’t been gutted and modernized; if it had been, he wouldn’t have given it a second thought.

Like many people who lived through the AIDS crisis, McGough looks on the current pandemic from the experience of that perspective — and with grace. Years back, he’d carry “a little blue glass bottle with a cork in it like the size for your palm, and it had vodka in it because that’s a hand sanitizer. I’m not a drinker, but I used it to sanitize my hands. You know, I almost died five times in my life. So I was prepared for it.”

Besides, “this apartment to me is like a living sculpture. I think of it as an art piece. It’s an environment, a whole attitude like it’s the 1930s but I’ve been here since the ’20s. The building is from 1905, and I have this little story in my head of how I have lived here; that’s my fantasy that keeps me going. I am not one of those people who like the minimalist block of wood as a coffee table.”

Source: The Cut