A Conversation with Friedrich Kunath

May. 29, 2018

By: Cody Delistraty

What changed in your work when you moved from Germany to Los Angeles a little over a decade ago?

It’s almost like once I moved to Los Angeles it became a full circle because I was missing something that I didn’t know existed, which is this kind of dimension of irony, stupidity, and silliness. Because in Germany you are so immersed in culture and seriousness so you carry your nature with you, all the memorizing, all this stuff that’s always around you.

There’s a certain levity to American culture then that you were able to tap into?

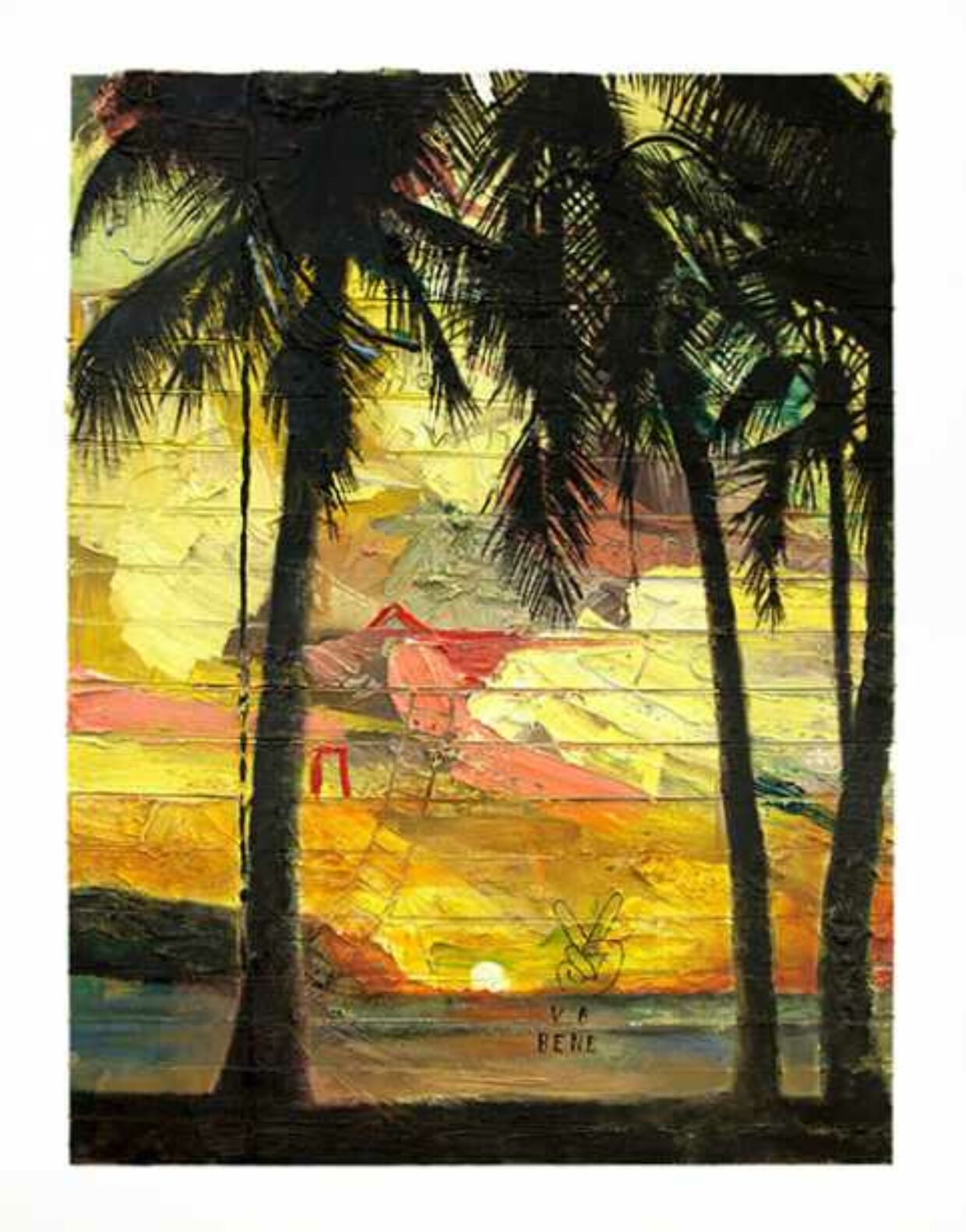

You have a hypothetical idea of [American] popular culture early on. That’s why people are so drawn to America. I think that is a reason why people crave it so much. There is some easiness there, but it’s in the distance. The kind of level of self-seriousness was clearly overwhelming me, and, living in Cologne at that time, it was unbearable because everything was a question of history. A left or a right brushstroke was an existential question, and you’d get criticized in the streets, stoned to death in the gallery. I think once I got there [to Los Angeles], my art almost emerged like a white, empty canvas. Being in a place where culture is Mickey Mouse and Charlie Chaplin, it’s exactly what I needed, and it was a revelation. It was a revelation to have surfing culture, to have breast implants…

Do you see yourself as working in a specifically Californian tradition?

I think in a place like California the collective dreams of us humans are manufactured. I absolutely see myself in the tradition there more than I see myself in the tradition of New York. And being a German painter in Germany, there’s a bigger narrative. It’s a global narrative.

Your work is automatistic, as if derived from your subconscious…

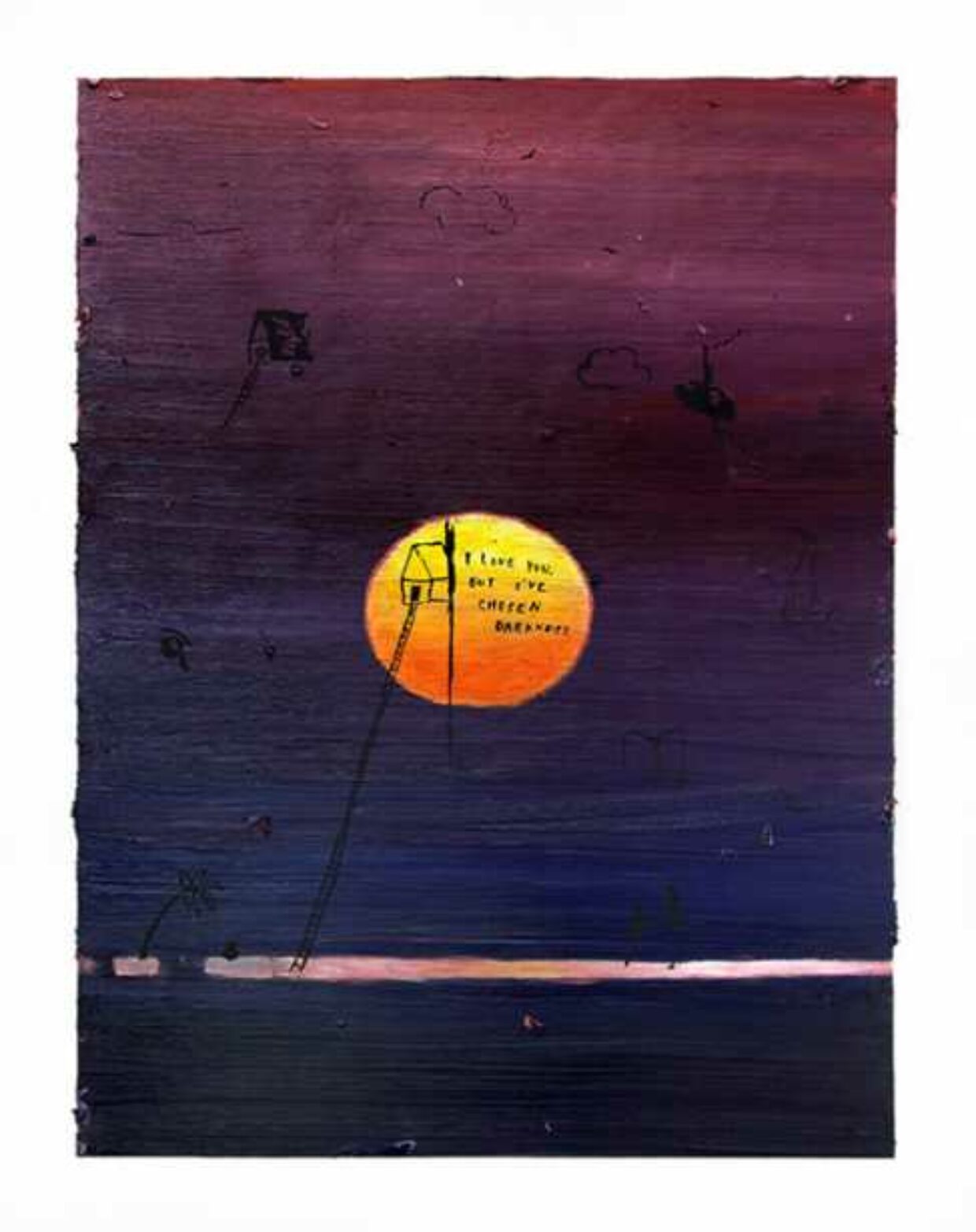

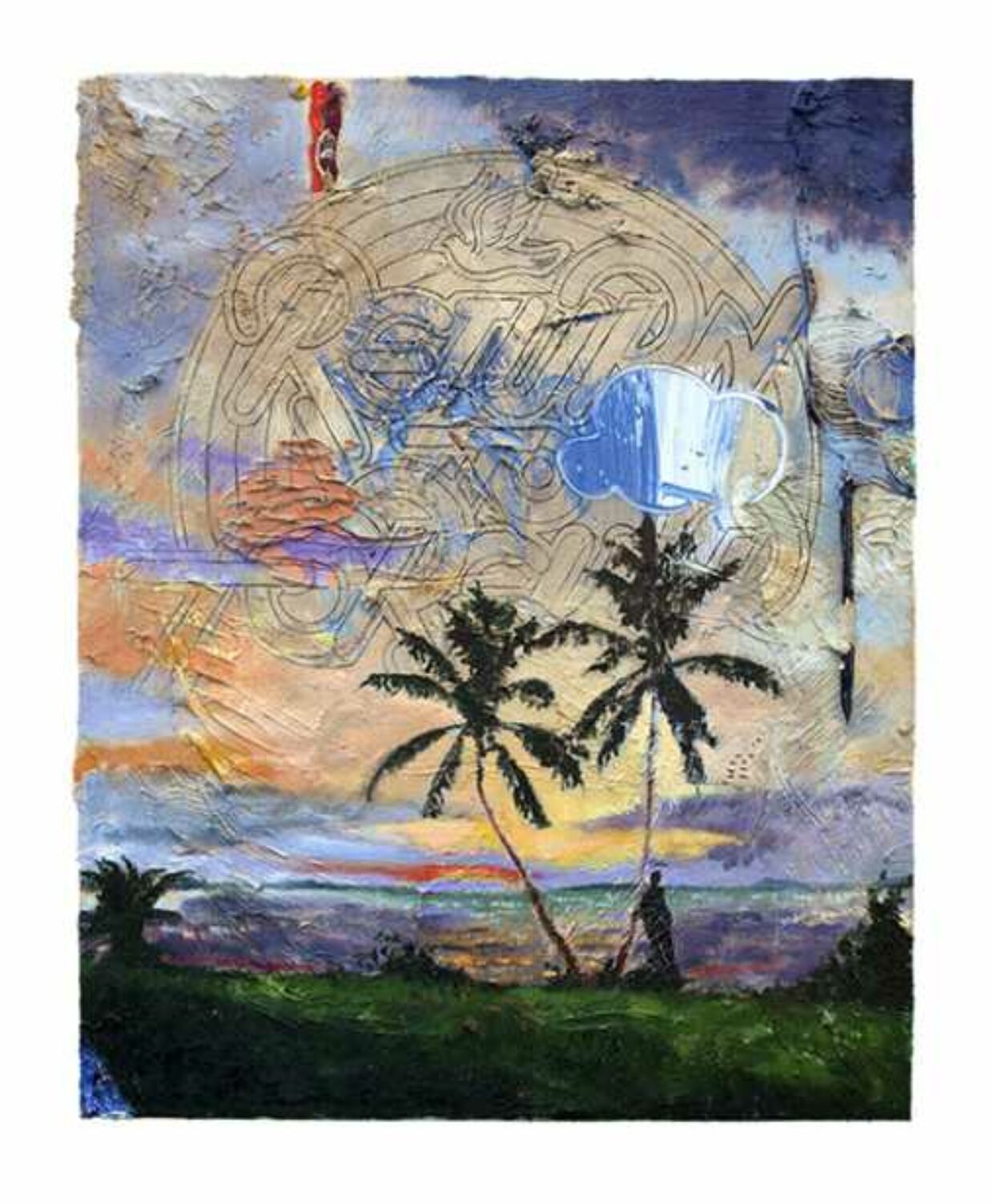

I began doing all these pictorial, tarot images, like sunsets, rainbows — things you were always not allowed to do [in Europe] because they involved that which is kitsch and all these questionable elements that were empty — hollow and meaningless.

But how do you avoid sentimentality?

I don’t anymore. I don’t avoid it. It is what it is; I don’t make a comment; I don’t judge it. I notice it and then I do it. I think that judging is not my job, that’s someone else’s job. My job is to paint it, but without suppressing it and that’s exactly what Los Angeles allowed me to do. It allowed me to notice and embrace. It just comes to me, and I just do it. I don’t question my motives anymore because that draws me into creating meaning and all that. All this, I gave up, and I just also wanted to be free of this.

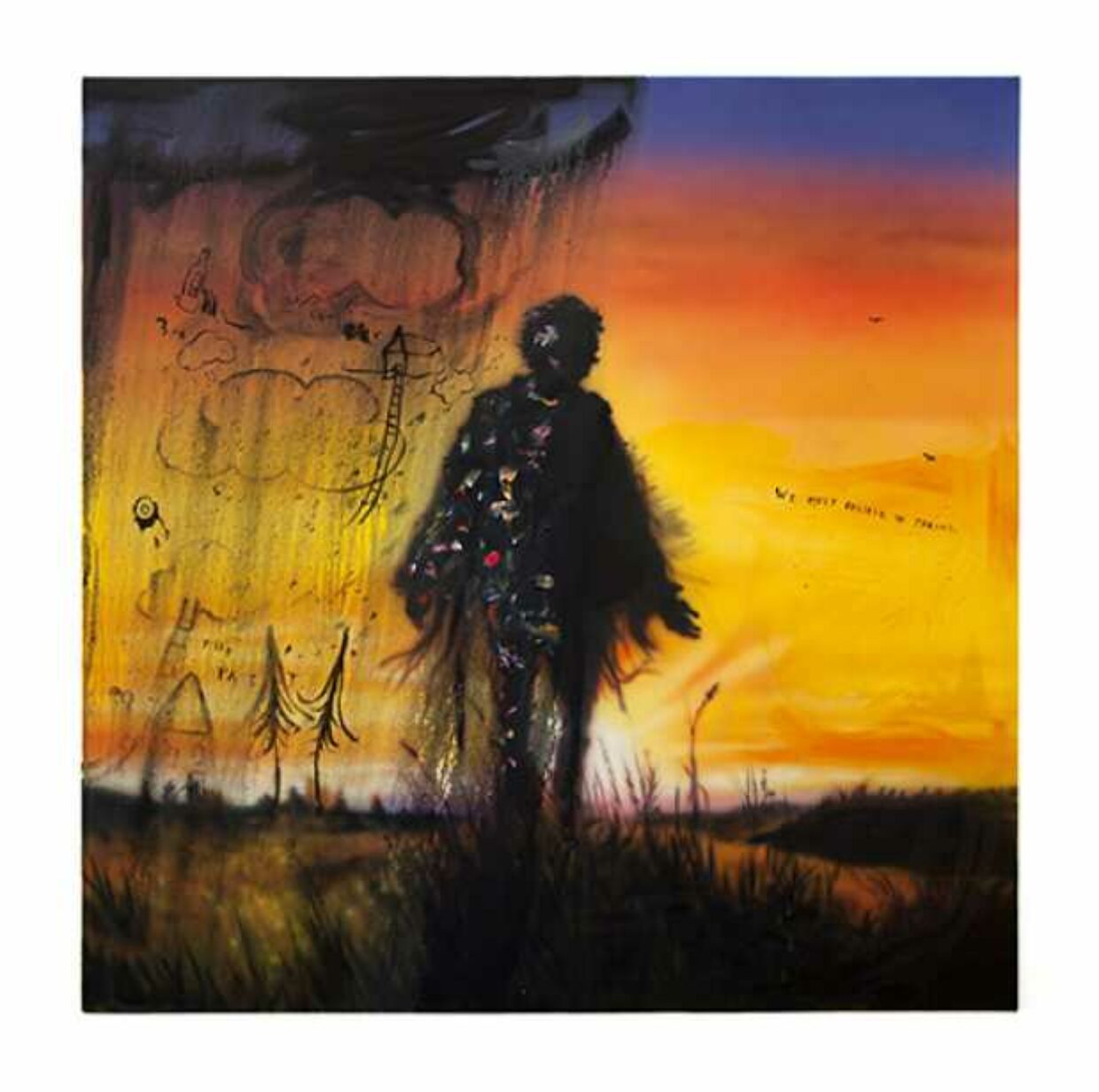

There’s another element to my idea of sunsets and pictorial settings that evokes sentimentalism. There’s — in my head — always the end scene of a movie, just before the credits begin rolling. That’s the very image I always think of, that’s where my painting is. My painting starts before the credit lines roll in. So that’s always been the evening painting, the afternoon, the autumn of life — that’s always been the reflective state of everything I wanted my characters to be. Everything I have inside, I want to project in there. So, culturally, this image has always been the sunset, the somehow-reflective state of a landscape, and the car driving into sunset and all the things, and I guess that’s why I’m so close to music. That just consoles me and confuses me to a degree I’m not able to express in other than what I do right now.

The sentimentality consoles you?

Yeah, all I consume is for pure consolation. I want to be understood. I read and I watch films and I listen to music not to solve intellectual inquiries. I want be heard. I want to be understood, and I want to understand, but at the same time there’s a big confusion that’s bigger than me that I don’t understand.

Your characters are deeply lonely and evocative of Edward Hopper’s lonely people. Are they also a reflection of you and of your interior confusion?

I just choose these characters by some unconscious thing. I go through them like a director goes through his cast. By looking at them they conjure something in me — something I’m not able to express; therefore I use them. Now the result is obviously not linear. They don’t solve anything in me; they’re just there. But it’s also not my job to direct them. My job is to give them an environment, and that’s what I create them and then they do the job anyways.

It sounds as though you think of your art cinematically more than anything else?

I never think about art too much on a big scale, but I think of music and film. I learned a while ago that I can get too much into art. I’ll get too depressed. But when I listen to music, and I research music for hours a day or look at films everyday it does so much more for what I do on a daily basis. I don’t sit in front of my canvas as a scholar about Vuillard. I mean, I know about Vuillard, but I’m actually not studying it. I study Bach or Glenn Gould or Keith Jarrett or Lady Gaga; it doesn’t matter. I’m high and low. I always compare it to that notion of when you look in the sky, when you focus on a really weak star, when you really focus on it, it disappears; but, when you look next to it, it’s there again, and I think that’s my relationship to how I treat art and how I deal with film and music. It leads to what I do and to this thing, but I’m not so much into it. An expert painter I’m not.

You’ve often said that academics find your art disconcerting, that your artistic transgressions go too far…

It puzzles me. I’m like “Are they mentally ill?” Who makes these rules? I mean, that’s crazy, but for them, it’s often very valid, and it’s their reality. For me, it is shocking because I think to myself, “Well maybe there are rules.” Really, I’ve been questioning myself and was like “fuck man, maybe I’m doing it all wrong.”

Would you consider there to be an overarching, cohesive style to your work?

I look at it, and I think, as with everything, it’s about context. Once you delve into the work of someone, there are so many connections you can make that it all becomes clear, or at least cohesive, like you said. In my case, my thread was never the formal aspect; it was always the emotional. That’s what holds it all together. It doesn’t matter if I do a sculpture or an oil painting or a spray painting. I think it’s all one song in terms of feel. The visceral is just really important. I get a lot of shit for it sometimes. It’s always cooler to say “fuck you,” than to say “I love you.” So although I play with irony, I always make sure there’s an earnestness with it. I’m not full of cynicism; I’m full of love. Although “love” in 2018 seems to be a corrupted word, but I still believe in the sense of it. I use irony as a technique, but it’s done out of a sincereness.

Source: Blouin Art