Kehinde Wiley: ‘When I first started painting black women, it was a return home’

Jan. 10, 2019

When the American artist Kehinde Wiley – known by many for his presidential portrait of Barack Obama – walked into a Little Caesars restaurant in St Louis, he didn’t know he’d walk out with models for his next painting.

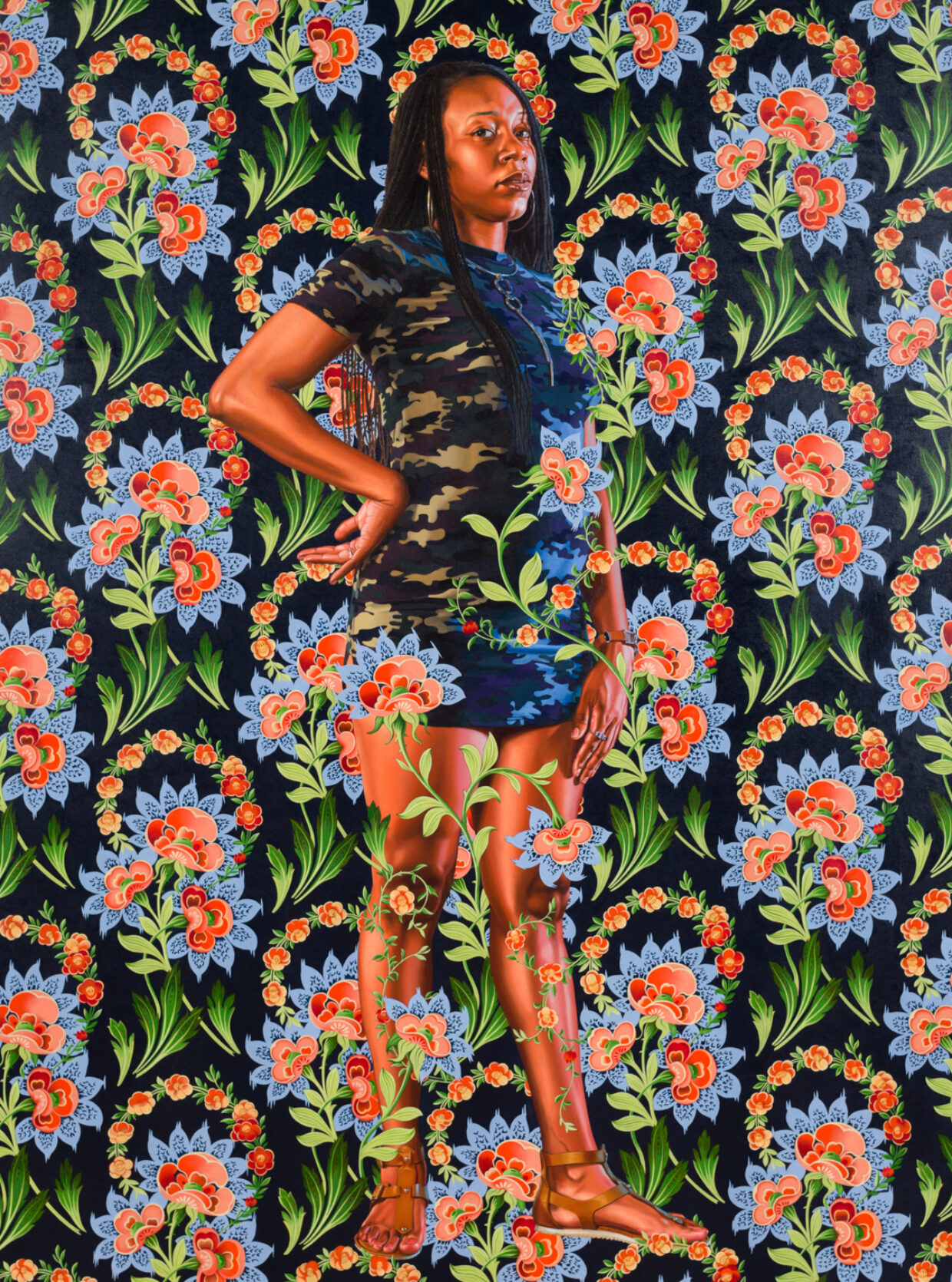

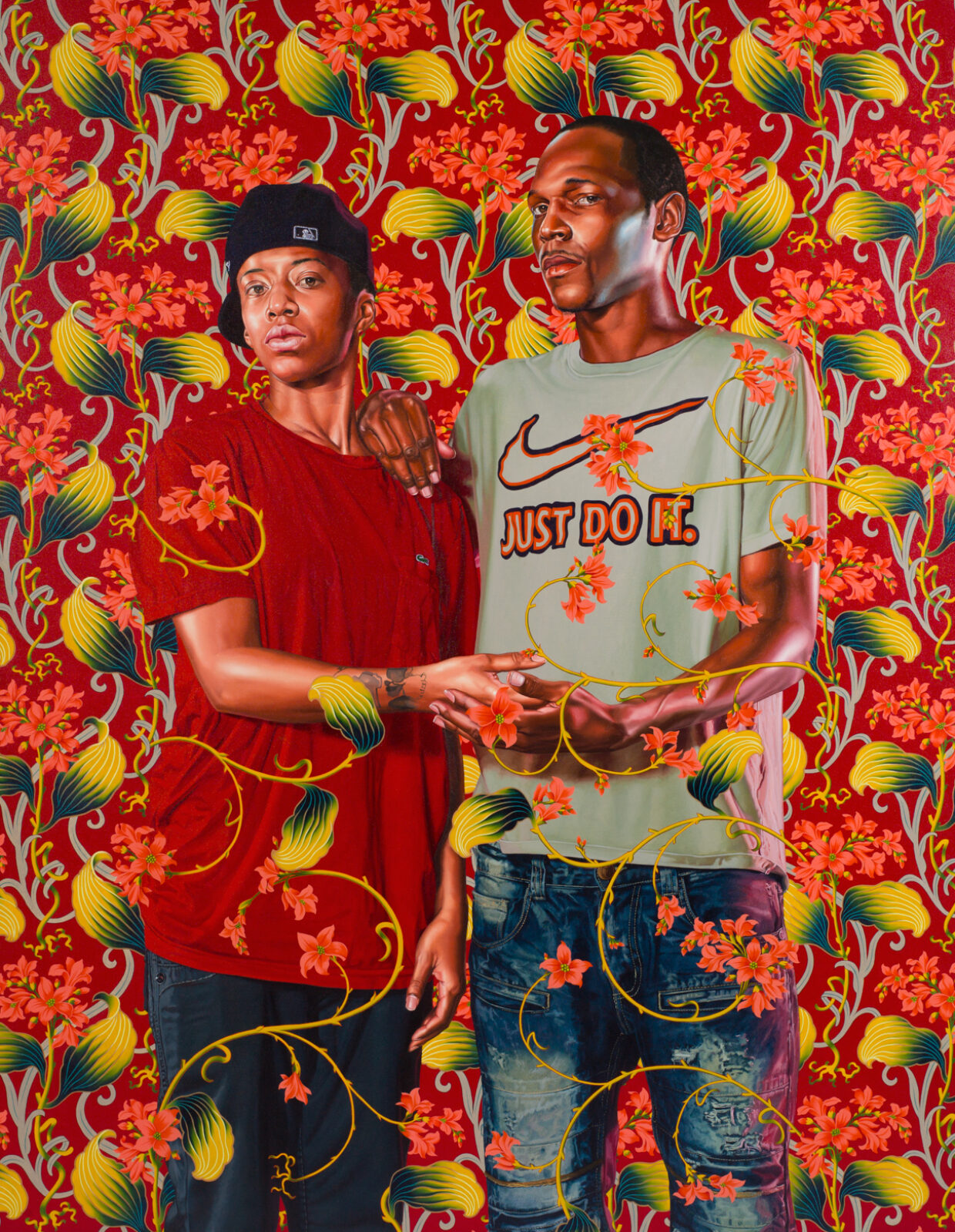

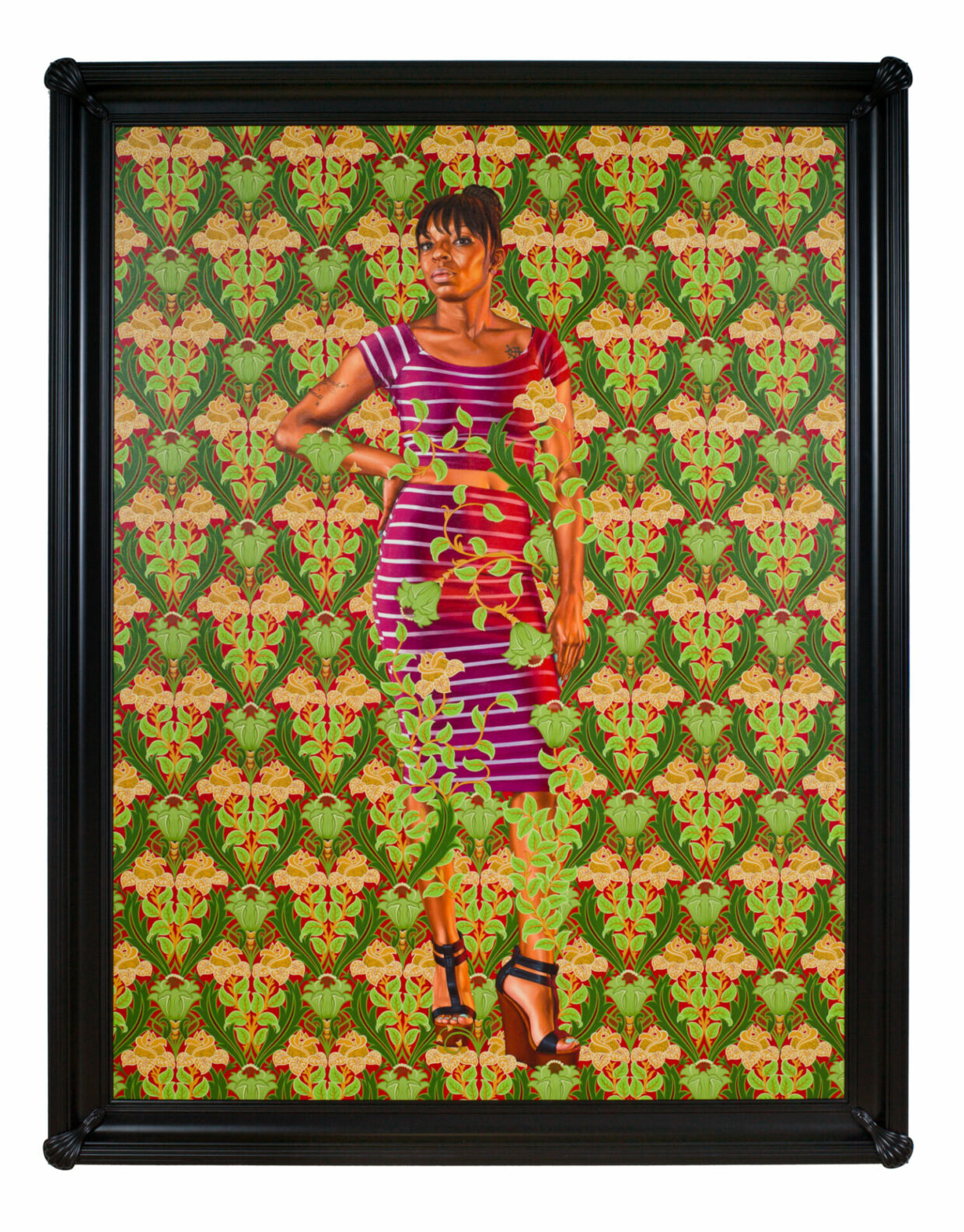

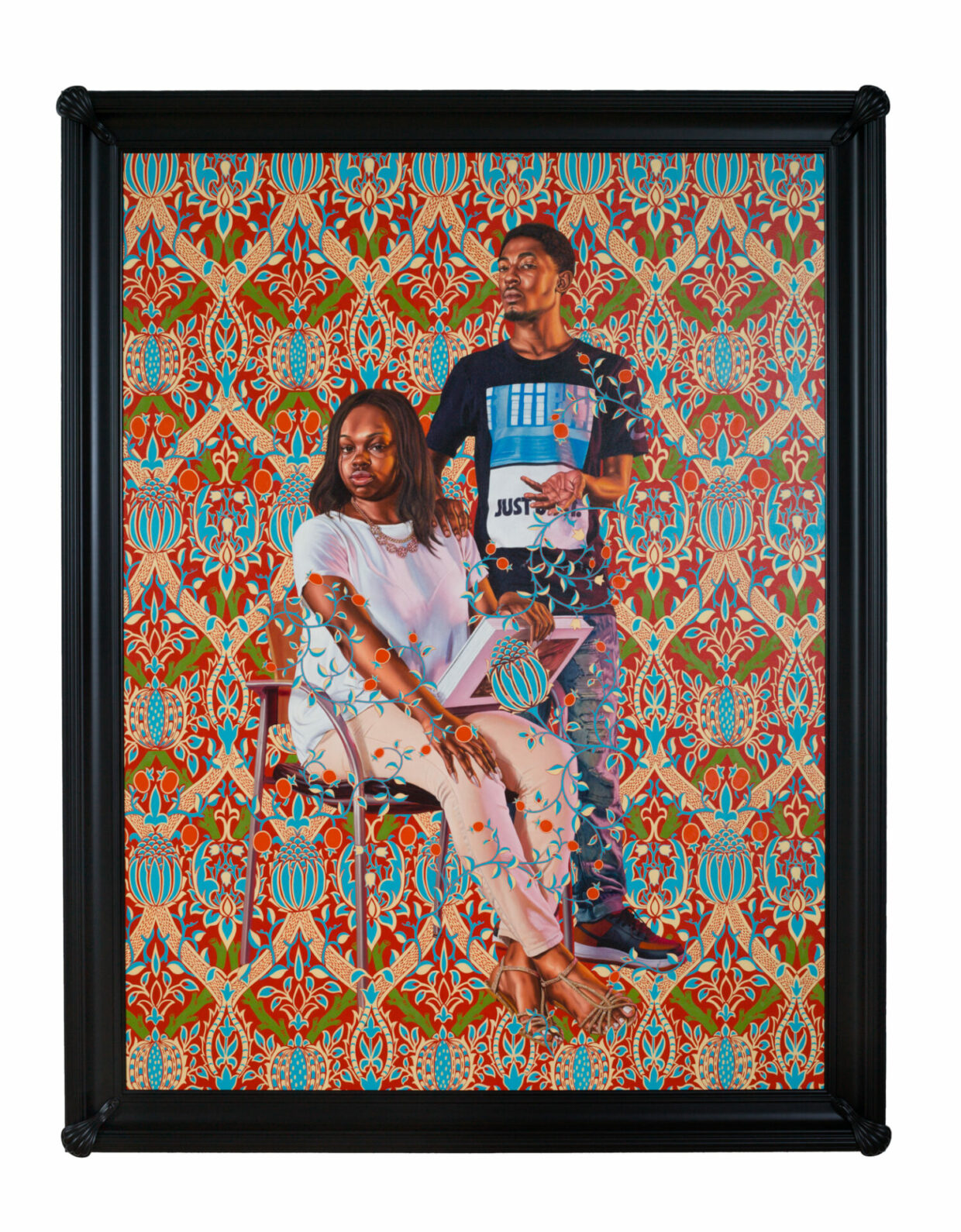

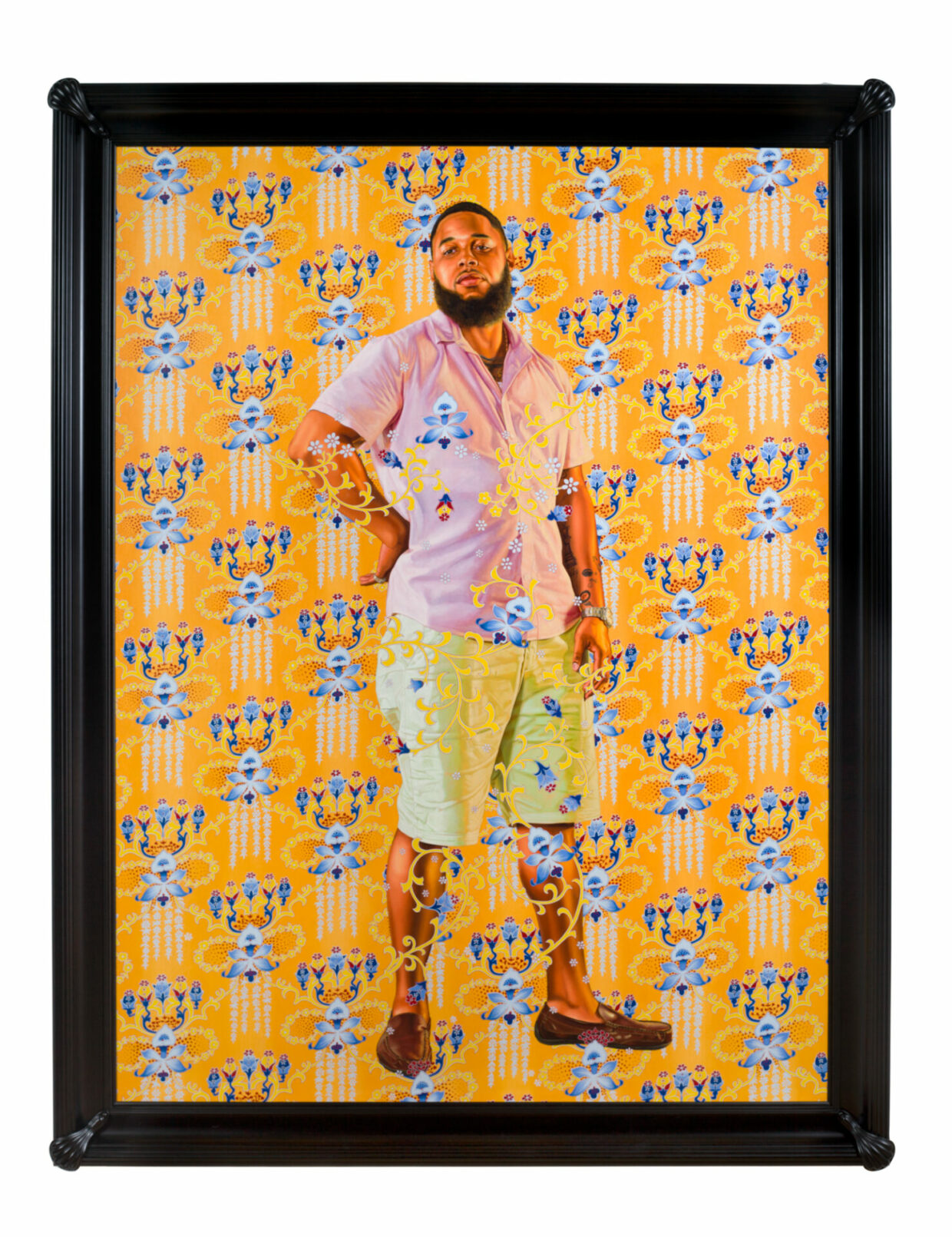

He saw a group of African American women sitting at a table and was inspired to paint them for Three Girls in A Wood, a painting on view at the St Louis Art Museum. It’s part of Wiley’s exhibition Saint Louis, which runs until 10 February, where 11 paintings of St Louis locals are painted in the style of old masters, a comment on the absence of black portraits in museums.

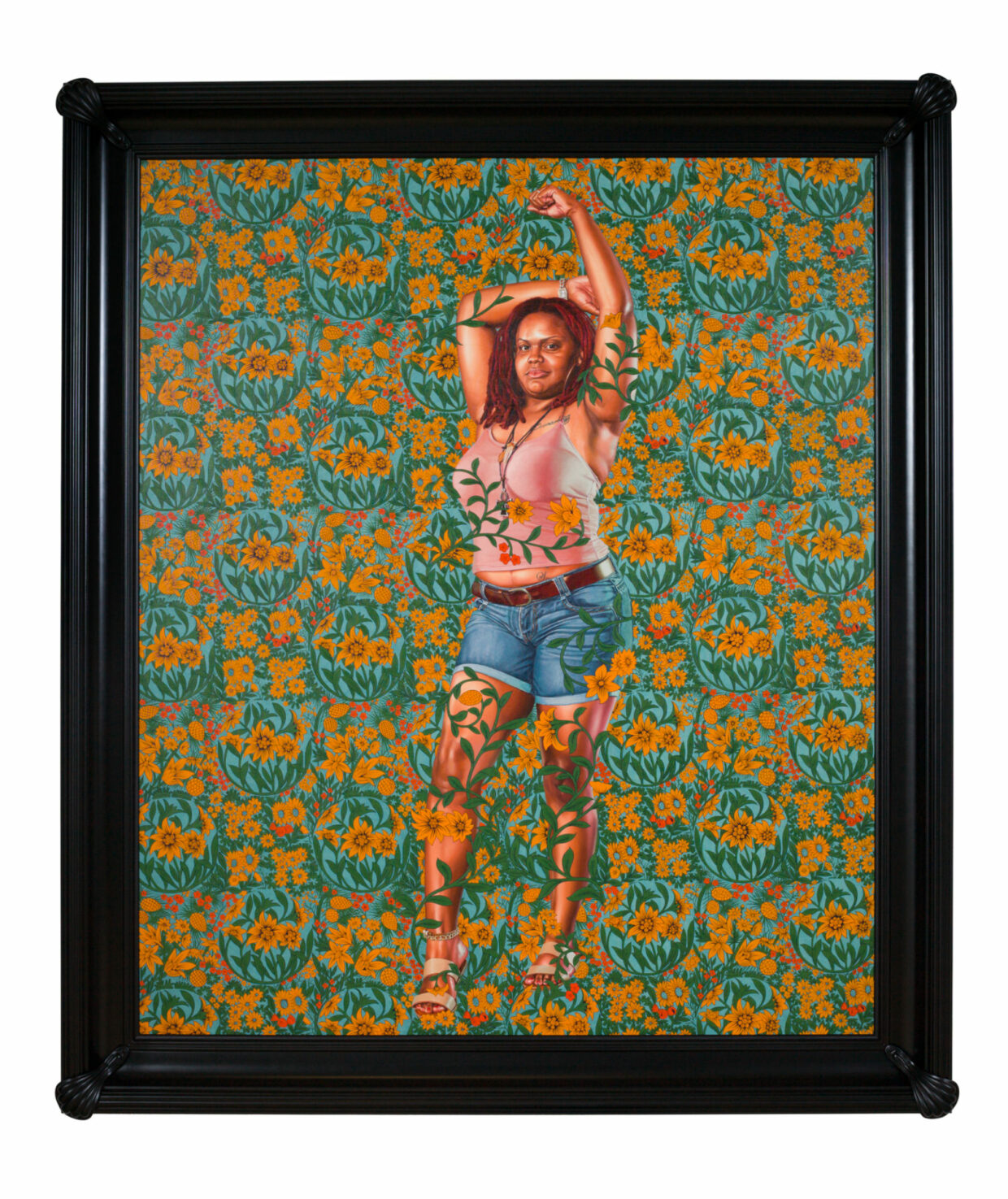

“The great heroic, often white, male hero dominates the picture plane and becomes larger than life, historic and significant,” said Wiley over the phone from his Brooklyn studio. “That great historic storytelling of myth-making or propaganda is something we inherit as artists. I wanted to be able to weaponize and translate it into a means of celebrating female presence.”

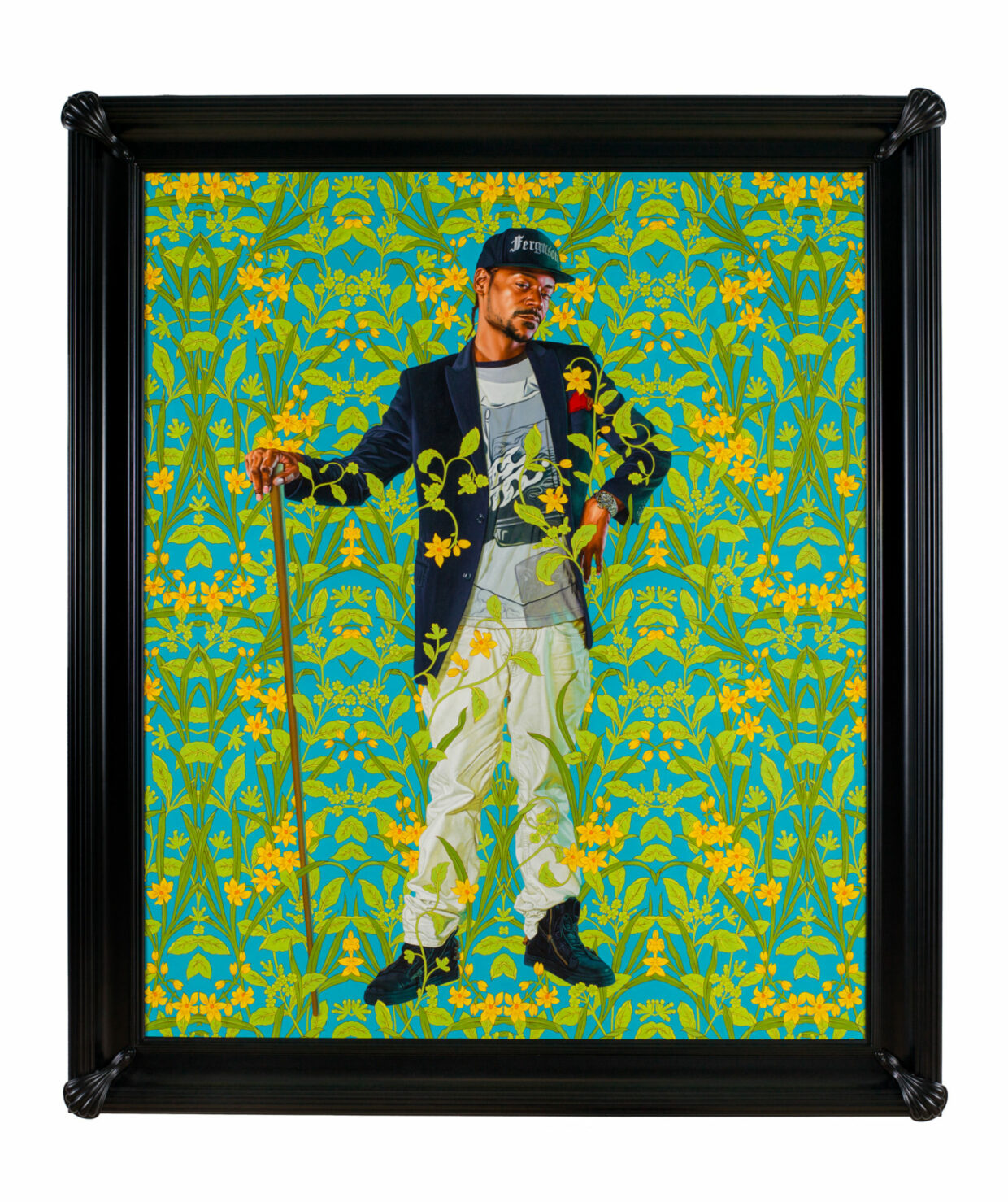

It all started last year when the museum invited Wiley to create an exhibition, which prompted Wiley to visit the museum’s sprawling collection. Noticing the lack of people of color on the walls, he ventured out into the suburbs for subjects to paint, including Ferguson, a hub of the Black Lives Matter movement since the police shooting of Mike Brown. (“There’s a very strong dissonance between this gilded museum on a hill and the communities in Ferguson,” Wiley recently said). He put out a public call and personally invited locals for a casting inside the museum.

“From the beginning, it was about a response to the museum as a strange metaphorical divide between the culture, not only in St Louis, but in America at large,” he said. “The kind of inside-outside nature of museum culture can be alienating and St Louis has one of the best American collections of classical works, so I wanted to use the poses from these paintings for potential sitters from the community.”

Wiley has painted St Louis natives as stately figures, wearing their day-to-day garb, even showing women in traditionally male poses. Shontay Hanes from Wellston is painted in the pose of Francesco Salviati’s Portrait of a Florentine Nobleman, while her sister Ashley Cooper’s pose is similar to that of Charles I in the portrait by Daniel Mytens the Elder.

As the models posed for him, Wiley took hundreds of photos, which he took back to his New York studio. He picked the photos that had the strongest presence and painted them. “My process is less about the original sitter, nor is it entirely about the individual,” he said. “It’s a strange middle space that is marked by a kind of anonymity, standing in for a history that is not your own. A pose that is not your own. There is a kind of complexity there that is not reducible to traditional painting.”

There is also a painting in the exhibit which mimics Gerard ter Borch’s portrait of Jacob de Graeff, which inspired Wiley’s portrait of Brincel Kape’li Wiggins Jr, who is wearing a Ferguson hat as a way of showing the city in a positive light.

Wiley, who grew up in South Central Los Angeles in the 1980s, had an a-ha moment when he first saw the works of Kerry James Marshall in a museum when he was young – it proved to him that African American figures belonged on museum walls, too. He studied painting in Russia at the tender age of 12, chased down his Nigerian father at 20, graduated from Yale in 2001 and has been painting African Americans – including a commissioned portrait of Michael Jackson – as old masters icons since the early 2000s.

“When you think of America itself and its own narratives, there are inspiring narratives and the notion of American exceptionalism,” said Wiley. “It’s the place where the world looks to for the best of human aspirations. That narrative is highly under question at this moment.”

Despite becoming royalty in his own respect, as Wiley’s star-studded lifestyle has him posing for selfies alongside Naomi Campbell and Prince Charles on Instagram, he sees his country differently now, compared with when he started painting professionally. “By virtue of our strength, we’re at this point of weakness and inability to see a lot of the folly that is set in the country,” he said. “I think there is an overbuilt privilege that starts to come into play and inability to feel empathy for perceived outsiders.”

Since his leafy Obama portrait was unveiled last year, his life has drastically changed. “I don’t have to explain what I do any more,” he said. “It makes it a lot easier, ‘He’s the guy who did that.’ It’s going to be on my headstone.”

As for his painting of three women he found at a pizza parlor, it’s a departure from where he first began – which was classically trained painting of white women. “So much of my upbringing as an artist was painting white women often displayed nude,” he said. “When I first started painting black women, it was a return home.”

While Wiley is known for choosing models that stand out to him, he can never predict what will work in the studio. But he does know one thing. “I think the starting point of my work is decidedly empathy,” he said. “All of it is a self-portrait. I never paint myself but, in the end, why am I going out of my way to choose these types of stories and narratives?

“It’s about seeing yourself in other people,” he said. “People forget America itself is a stand-in for a sense of aspiration the world holds on to. It’s a really sad day when the source of light criticizes light itself.”

Source: The Guardian