Artists in a Post-George Floyd, Mid-Pandemic World

May. 17, 2021

By Aruna D’Souza

Two shows that recently opened at the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art are keyed to our new normal: One came into being during the most restrictive moments of the pandemic; the other, though long planned, shifted its focus as these past, momentous months unfolded. Conceptually, both address the questions — personal and political — that are on many minds at the moment.

‘Close to You’

This exhibition is a balm after a year in which so many had to learn how to maintain connections with loved ones in new, unfamiliar ways. In the early months of the pandemic, Nolan Jimbo, a graduate student in art history at nearby Williams College, selected six artists of color, many of whom are queer, whose work reflects on bonds of kinship and family, and on ways that those bonds can be created and nurtured across distances of time and space. They are Laura Aguilar, Chloë Bass, Maren Hassinger, Eamon Ore-Giron, Clifford Prince King and Kang Seung Lee.

Hassinger’s “Love” (2008/2019) is a welcoming entry point to this small but tightly packed show. Pink plastic shopping bags, attached to the wall, are filled with love notes and “inflated with human breath,” functioning as expressions of care that can be experienced when touch is impossible.

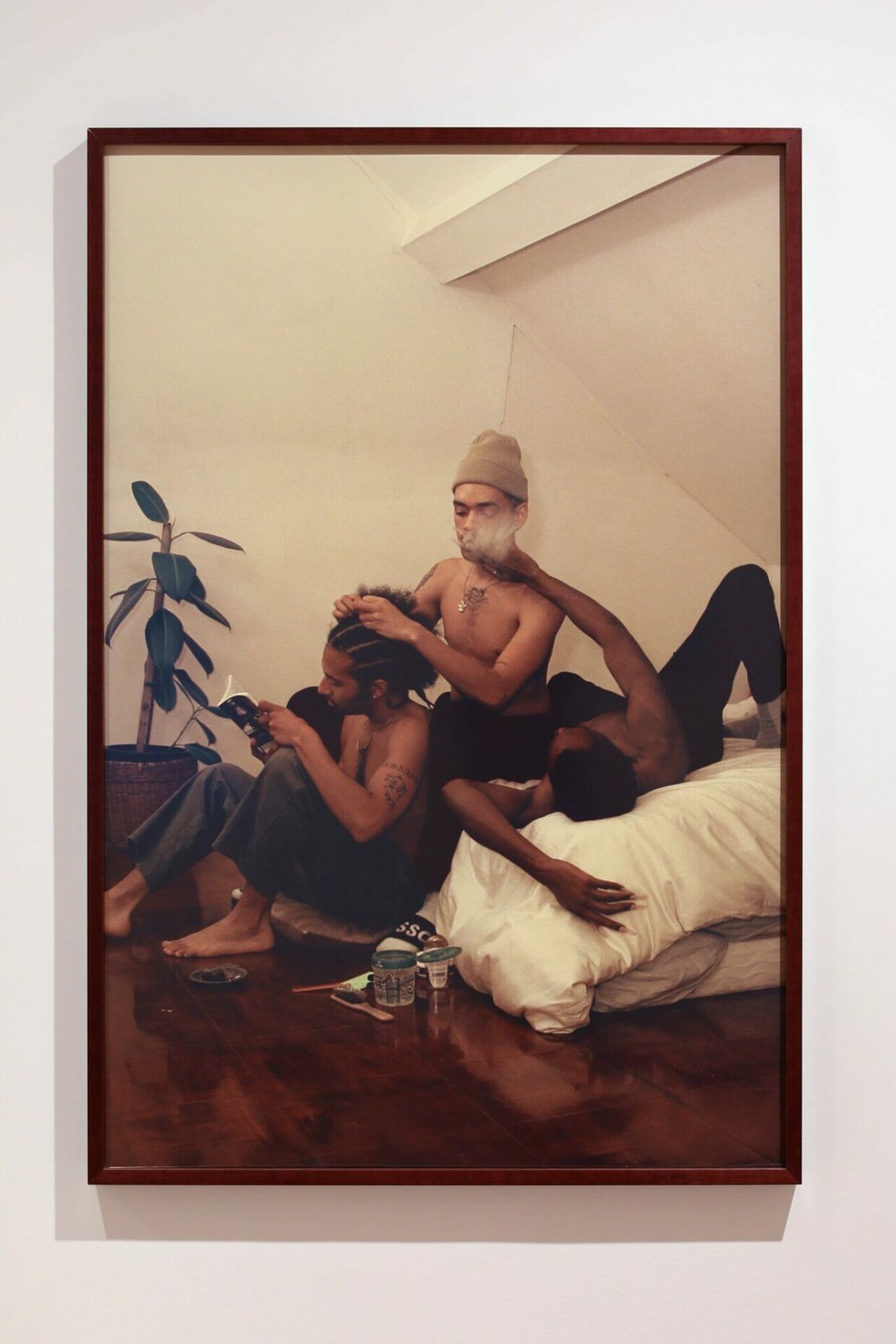

A contrast is found in the photographs of King (whose work has also appeared in The New York Times). Called “affirmations,” this series is about the subtleties of human contact. Two men dance in a kitchen; two figures kiss under a sheet as a light illuminates their makeshift tent from within; three men braid one another’s hair and smoke weed on a bed; others embrace the trunks of palm trees. These members of King’s inner circle seem to speak a secret language of touch to which the viewer is not entirely privy.

In other work on view, the notion of connection is more abstract. Laura Aguilar, the Chicana artist who died in 2018, photographed her queer, fat body in a landscape because she felt accepted by nature in ways she did not by other people; gelatin silver prints from her 1999 series “Stillness” are haunting and intimate.

The video, prints and poster that make up Bass’s “#sky #nofilter ” (2016-17) poetically suggest that our shared experiences — among our families, our friends, our political comrades — may not in fact be as communal as we imagine. Using a series of images of the sky, shot with an iPhone camera, Bass points out that even the most basic of statements (“the sky is blue”) must be examined in the face of our deeply individual responses to the world.

Lee creates imaginary genealogies of queerness. In his video, “Garden” (2018), for example, he imagines a kinship between the Korean writer Joon-soo Oh and the English filmmaker Derek Jarman — two people who did not know each other but whose work is meaningful to Lee himself. Lee digs holes in Namsan Park, a gay cruising spot in Seoul that Oh frequented, and in Jarman’s garden in Kent; into each hole he drops half of a drawing, connecting the two on a subterranean level.

‘Glenn Kaino: In the Light of a Shadow’

Glenn Kaino, a Japanese-American artist based in Los Angeles, began planning his installation for MoCA’s football-field-size Gallery 5 five years ago. He intended to draw a connection between two distinct “Bloody Sundays”— the civil rights march in Selma, Ala., on March 7, 1965, and the protest in Derry, Northern Ireland, on Jan. 30, 1972.

As time passed, the pandemic imposed limitations on the planning and execution of the piece, and the protests following the murder of George Floyd last spring added new context for the work.

The centerpiece of the show requires a slow, choreographed procession down an elevated boardwalk in the darkened gallery, with music and lights cuing viewers to move or stand still. Sticks and stones — the paltry weapons wielded by the Irish resisters — and found postcards hang from the ceiling or are raised off the floor by thin rods. Theatrical lights cast their shadows onto the wall, transforming the objects into birds, drones, sailing ships and meteorites by turn.

A wooden boat looms over the walkway — an allusion to the assassination of Lord Mountbatten by a faction of the I.R.A. in 1979. It is twisted, resembling a snake eating its own tail. Projected silhouettes flashing and rippling across the walls recall the murder of innocents by their oppressors. Puppetlike protesters carry signs — “Civil” “Rights,” “Association,” “Black,” “Now,” “Climate Action” — as if the language of revolution has been broken down into its most basic components.

At the end of the spectacle is a mirror in the shape of the masonry wall in Derry where the British army massacred Irish protesters. As the lights come up, a crowd of viewers sees a rippling, distorted reflection of itself — turning this accidental grouping into a potential for future resistance and protest.

In a separate room, a video made in 2020 centers on Kaino’s longtime collaborator, Deon Jones, who was shot in the face with a rubber bullet by a police officer while taking part in a peaceful protest in Los Angeles. Interspersed with photos of Jones in an emergency room and archival footage of the Selma and Derry events, Jones sings “Sunday Bloody Sunday.” In the video, he stands inside “Revolution” (2020), a round, cage-like sculpture that fills the space.

The astronomical imagery, the circular boat, the loop of protesters from different eras fighting for different causes: Taken together, the installation offers up the idea of political uprising as an inevitable part of the human condition.

This may feel fundamentally true after last year’s protests in Minneapolis seemed like a repetition of those from Ferguson in 2014. But Kaino’s thesis is also seriously depressing: People are not forced to fight for change because it’s written in the stars, but because those in power will not loosen the death grip on their lives.

Source: The New York Times