Francois Halard’s Newly Published Polaroids Open a Window onto Artists’ Homes, Including Cy Twombly’s

Jan. 30, 2018

By: Max Lakin

For the past 30 years, photographer François Halard has shot the lushly upholstered interiors of many notable personae, from Richard Avedon’s Montauk compound, to the seat of the Duke of Devonshire at Chatsworth House, to David Hockney’s LA swimming pool, making glossy tomes and Vogue spreads out of secret gardens and personal Arcadias. Halard shoots on film, but often takes Polaroids as a kind of study, or, more often, as a private souvenir. Polaroïds Italiens, published recently by Oscar Humphries in collaboration with Sotheby’s and IDEA, collects the photographer’s snapshots, made in Italy since the 1980s. They’re on an intimate scale that his commercial work doesn’t allow; painterly, impressionistic images previously kept only as a personal archive, they’re closer to sketches of feelings than lucid photographs. A shoebox of stolen glances.

The selection in Polaroïds Italiens is abbreviated, a handful of images of eight or so sites, a peek, really, like hazy memories of a dream. The images are all misdirection, tight crops, and oblique angles. In one, Halard lets a window fill the frame, the blistering sunlight evoking a mystic portal. In another, the Teatro Farnese in Parma appears flattened, making it hard to be sure you’re not looking at a postcard image of a pre-Raphaelite painting. “It’s more like a memory,” Halard told GARAGE. “Sometimes I look more at my old Polaroids than the subject by itself. I am very attached to objects, and the Polaroid is also like an object—offering the possibility of speaking about the past and the present at the same time.”

Halard’s Italian Polaroids are haunted by the ghost of painter Cy Twombly. Halard is something of a Twombly acolyte—he recalled buying a lithograph from the artist’s Roman Notes series with his first professional paycheck, and purchased his house in Arles because it reminded him of Twombly’s in Gaeta. Halard traveled to Gaeta in 1995 to meet with the object of his admiration, but his enthusiasm wasn’t immediately reciprocated. “Cy was very private, so it was a long approach,” Halard said. “I spent 15 years of my life waiting to spend a day with him. It’s funny because Polaroid means instant photography, but sometimes for the subject to be instantly photographed, you have to wait 15 years.”

Toward the end of his life, Twombly used Polaroids in his own art, making fuzzed-out still lifes of lemons and strawberries, distorted into expressive approximations of color and texture. Halard’s Polaroids internalize this sensibility, imparting a level of abstraction into each composition. What we see of Halard’s time in Gaeta, aside from twinned portraits of Twombly, sun-dappled and at ease in white slacks and suspenders, are tight details of works in progress: blooming red nimbuses and furious whorls of blue, more suggestion than documentation.

For Halard, the locales of Polaroïds Italiens are like devotional sites, the photographer a supplicant making his dutiful pilgrimage. At the Grizzina house where Giorgio Morandi spent his summers, frozen in time since 1963 and now maintained as a museum, Halard lingers on the studio’s details: paints and tools, and the vases and vessels mirrored in the Morandi still life hung above them. Halard’s images form their own still lifes, a surreal mise en abyme, the Polaroid even aping the same soft pigmentation and chromatic subtlety that Morandi favored. “I always tried to remember the work of the artist,” Halard said, “to be almost as if I were Morandi making a Polaroid of my own atelier.”

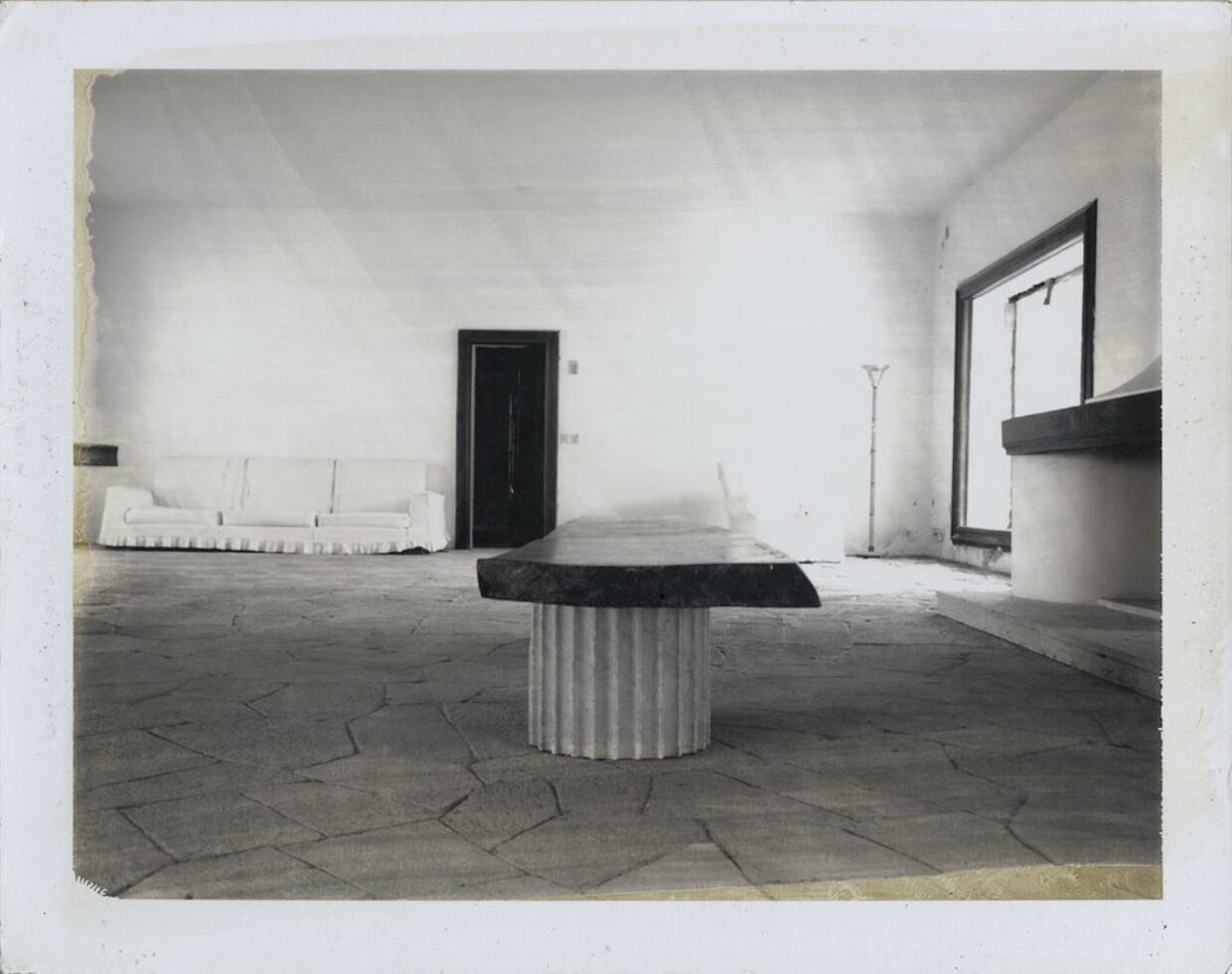

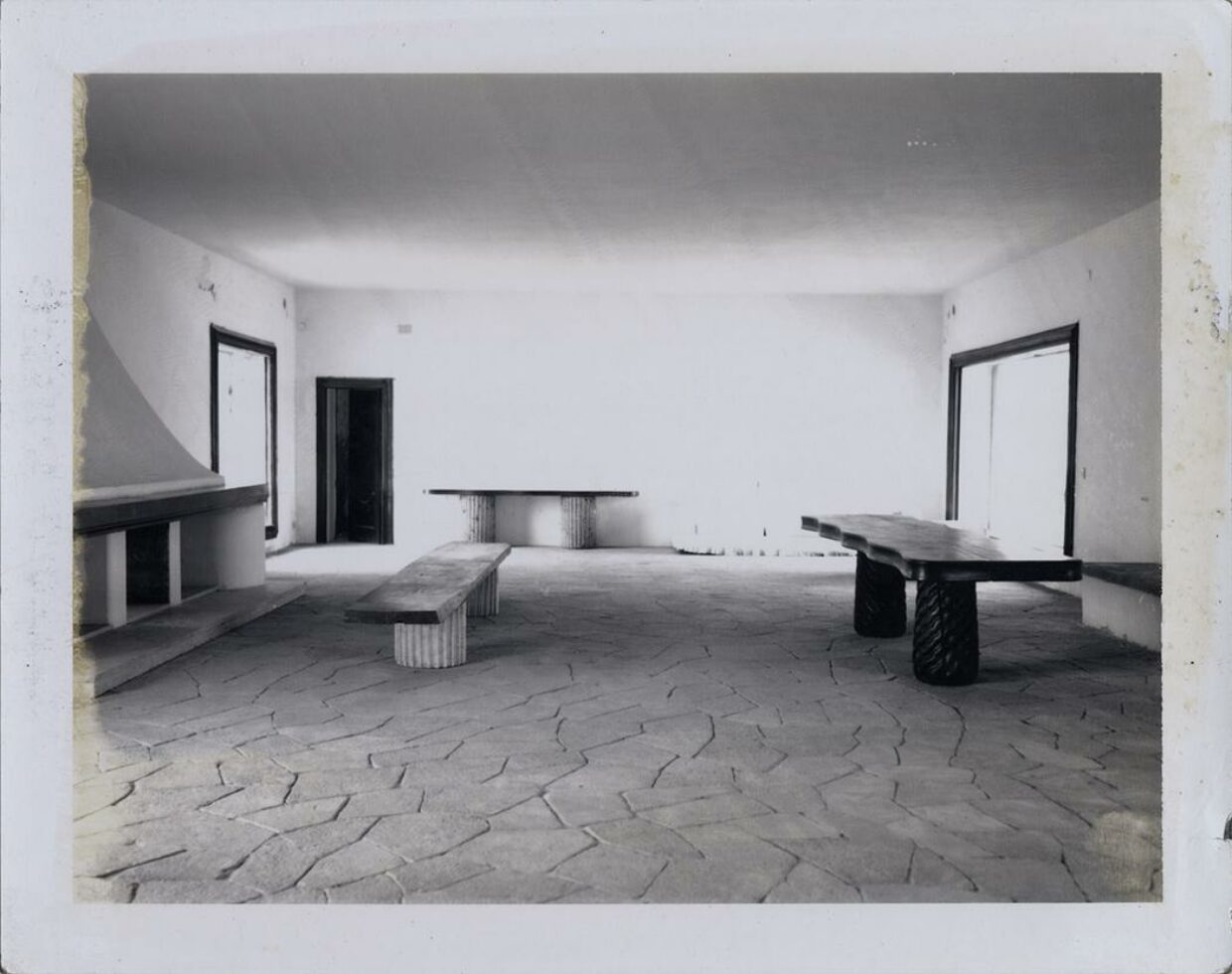

Visiting writer Curzio Malaparte’s modernist Capri villa, where Godard filmed Contempt, Halard shoots the low-slung lines of the interior as a washed-out fantasia. The stepped facade, where Brigitte Bardot suns herself languorously, reaches into the air before being obliterated in the light. “I had a complete fixation with that house. Totally obsessed. Malaparte was my favorite writer, and it felt very familiar. And I think with both Malaparte and Twombly, their houses are the best reflection of who they are, truly. It’s like a mirror.”

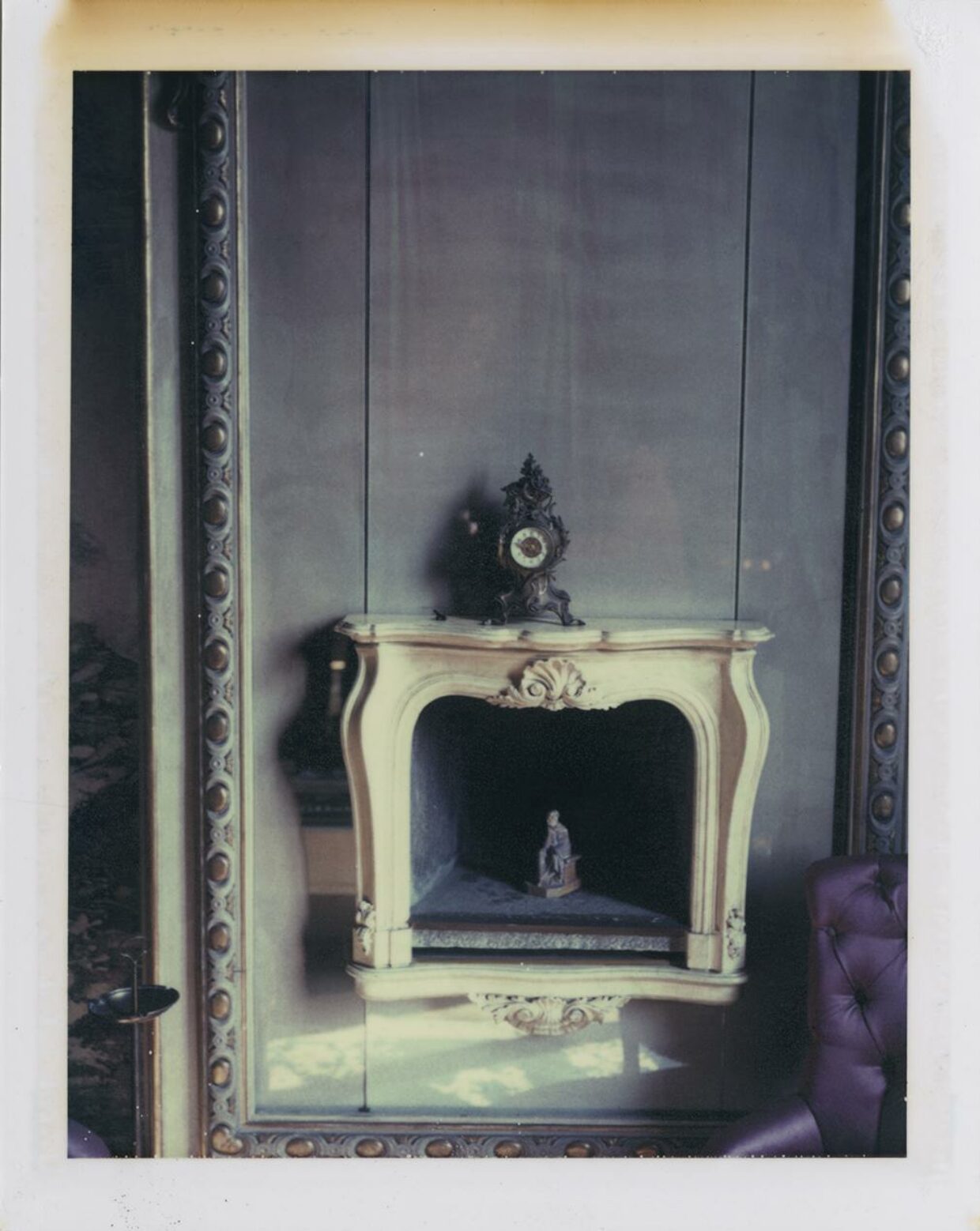

At architect and designer Carlo Mollino’s 19th-century apartment in Turin, the existence of which he guarded so fiercely that he never spent a night there and few even knew he owned it until after he died, Halard doesn’t resist the rococo interiors (“erotic maximalism” is a good start; in one room, the walls are leopard pelt). As a destination in Halard’s grand tour, and as a theme for Halard’s work, Casa Mollino makes sense; Mollino carried on an obsessive Polaroid practice in which he invited women there after hours, making elaborate, tastefully pornographic pictures in which bodies were more of an accessory to the voluptuous interiors. That’s because the interiors existed explicitly and entirely for that purpose—designed to be the background of his fantasy, to be photographed.

Francois Halard: Polaroïds Italiens is published by Oscar Humphries in collaboration with Sotheby’s and IDEA, in celebration of the December 2017 exhibition François Halard: Polaroïds Italiens at Sotheby’s London.

Source: Garage